Weaving Bridges and Bonds: Japan Travel Experiences, Traditions, and Treasures

A blast from a conch shell cut through the canyon. Two men in white wool jackets and brightly colored chullo caps placed a glistening llama fetus atop the glowing embers of a fire still feeding on a bloody sheep‘s heart. As they lifted their hands to the heavens in hopes the gods may accept the offering, Victoriano Arizapana slung a golden coil of rope over each shoulder, and walked toward the edge of a cliff. A hush fell over the sea of sombrero-clad men who parted as the 60-year-old slowly approached the abyss.

With a deep breath, Arizapana carefully lowered himself onto four tightly braided cables, spanning the 30-meter crevasse, each the circumference of a man’s thigh, and straddled them with his bare feet, dangling over the sides. He then poured a few drops of clear cañazoliquor on each cable, whispered the names of the four mountain spirits who would decide his fate, and pushed himself off the end of the stone abutment into the gaping chasm.

That’s how Eliot Stein begins his riveting profile of Victoriano Arizapana, the last Inca bridge master, in his extraordinary new book, Custodians of Wonder.

High in the Peruvian Andes, Victoriano fulfills a duty that men in his family have maintained for more than 500 years: leading the reconstruction of the only surviving Inca suspension bridge. This bridge is fashioned from a straw-like grass called q’oya ichu, which has been harvested and tightly woven by members of the four local communities. By tradition, this task must be done every year, and it must involve not just Arizapana but all the residents of the surrounding villages. This practice dates back to the Inca Empire and manifests the communities’ enduring connection to nature and to their own defining beliefs and traditions.

Eliot’s account eloquently depicts Victoriano’s death-defying role and also explains the larger meaning of that role and of the woven-grass bridge as a whole. And Victoriano is only one of the custodians who are profiled in this book. In nine more chapters, Eliot crafts equally vivid descriptions of people who are practitioners – in many cases, the last practitioner — of some of our planet’s most ancient cultural creations and rites. These include:

A 27th-generation historian-storyteller from Mali who, through his remarkable memory and mastery of the traditional balafon musical instrument, is a kind of living library, preserving and sharing the history, stories, and music of his West African ancestors.

The last official Cuban cigar factory “lector,” whose venerated job is to read news, announcements, and literature every day to all the cigar-rollers, -sorters, and -stemmers in the factory as they work, a tradition that has educated and entertained laborers for over a century.

A woman in southern India who carries on her family’s ancient craft of melting tin, copper, and other metals in a special formula to create the Aranmula Kannadi, a mysterious metal mirror that is believed to reveal one’s truest self.

The Japanese guardian of a 700-year-old soy sauce recipe and fermentation process, who is passionately dedicated to preserving its secret ingredient.

Custodians of Wonder is a profoundly moving and inspiring book, and it has made me think with renewed gratitude and appreciation about some of the artisans we are privileged to visit on the GeoEx trips that I lead: backstrap loom weavers and ceramic artists in Mexico, potters and washi paper-makers in Japan, tanners and olive oil producers in Greece. Like the people Eliot profiles, these artisans are treasures who preserve precious cultural traditions and creations.

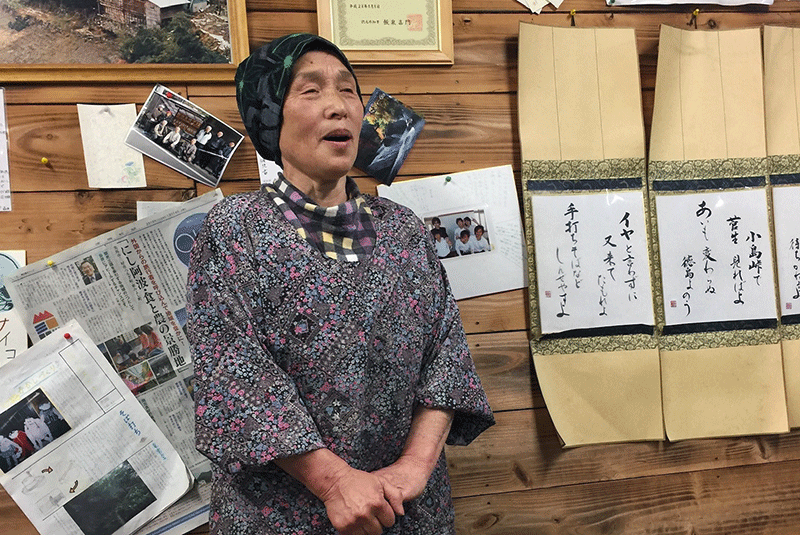

In particular, I have been remembering my first encounter with an elfin, agelessly energetic woman named Reiko Tsuzuki, who lives in a virtually impenetrable region on the island of Shikoku, the fourth largest and least visited of Japan’s four main islands. Tsuzuki-san is both a legendary soba maker and an award-winning singer of traditional folk songs, but I didn’t know any of this when I first met her.

Discovering Japan’s Hidden Treasures

On GeoEx’s inaugural Journey through Ancient Japan trip in 2013, we ventured deep into the heart of Shikoku’s Iya Valley, a region whose forbidding slopes and one-lane-wide, tortuously winding roads have kept all but the most determined visitors away for centuries. On that adventure we discovered breathtaking mountain and river scenery, awe-inspiring vine bridges, rugged hillside villages with thatched-roof farmhouses, and crusty, kind villagers.

And we discovered Tsuzuki-san. In Iya, our local guide explained as our van wound toward Tsuzuki-san’s soba-making workshop-restaurant, the precipitous slopes, poor soil quality, and severe weather have made rice-planting impossible, so for centuries the local farmers have grown buckwheat instead. For this reason, making buckwheat noodles — soba – is a great way to experience firsthand one of the oldest culinary traditions in Iya. And, our guide continued, there is no better teacher than Tsuzuki-san, who was born and raised right here and has been making celebrated soba for four decades.

When we arrived, Tsuzuki-san and her two sprightly helpers – all of whom looked to be in their 70s – led us into her workshop, helped us don multicolored aprons and head kerchiefs, and then taught us the fine art of soba-making.

Traditional Soba Making: A Hands-On Cultural Experience

The first step was to grind buckwheat seeds into flour. First three of us knelt around a traditional ishiusu, or millstone. This consists of two heavy circular stones, about six inches high, one stacked atop the other. The top stone has a hole about two inches in diameter in its surface and a wooden turning stick about two feet long that is attached to the side of the top stone.

As one of us gently pushed the kernel-like seeds into the hole in the top stone, we all worked together, each with one hand on the turning stick, rotating the top stone and slowly, laboriously grinding the seeds into flour.

After we had produced a discernible dusting of flour, Tsuzuki-san and her helpers added our production to a community-sized bowl of flour they had made before our arrival, then scooped that flour into smaller bowls which they distributed to each of us. She then told us to mix cold water slowly with the flour and to stir the mixture in a circular motion to distribute the moisture evenly. When the mixture starts clumping, she said, we should knead it firmly but gently into a smooth, elastic ball.

Next she handed us all rolling pins and showed us how to flatten the ball until it resembled a buckwheat pizza about three-quarters of an inch thick. Then, following her instructions, we picked up the dough, lightly sprinkled it with flour to prevent sticking, folded it accordion-style in half and then in half again, and finally used a special soba-cutting knife, called a soba kiri bōchō, to cut it into thin, even strips about half an inch in width.

We stumbled and fumbled through these steps, laughing at the ragged pizzas and bulbous soba strips we were making, sprinkling as much flour on ourselves as on our dough. Our guides led us every step of the way with good humor and generous doses of laughter, and occasionally burst into applause when one of our group performed a task with special skill.

After we had created our earnest, amateurish soba strips, we transferred them to bamboo platters and carried them to a huge pot of boiling water. There, being careful to separate the strands as much as possible, we dropped them into the bubbling water. We boiled them for a minute, then lifted them out using a soba sukui — a specially designed wire mesh strainer — and placed them into a pot of cold water. (By this time, I was realizing that the fine art of soba-making has inspired its own subset of special tools.)

Two minutes later, as our teachers triumphantly lifted up the soba strands, glorious and glistening, and arranged them on bamboo trays to be carried to the kitchen, one of our group spontaneously exclaimed, “Wow! I have a whole new appreciation for soba now!”

I translated this for Tsuzuki-san and she smiled. “I learned this from my mother, and my mother learned it from her mother,” she said. Then she paused and turned to face the guest who had spoken. Her eyes sparkling, she said, “Now you’re part of our family!”

Following Tsuzuki-san, we walked 10 steps from the workshop to her home, where tatami mats and low wooden tables awaited in a living-dining area that could comfortably accommodate two dozen guests. There we feasted on a delicious home-cooked meal that featured the soba we had just made and vegetables that Tsuzuki-san said she had picked from the surrounding hillsides at 5 am that morning.

This entire experience – making noodles under the guidance of Tsuzuki-san and her friends in the workshop, then feasting in her home on those noodles and the vegetables she had freshly plucked from the hillsides around us — forged a delicious and indelible bond. As Tsuzuki-san and her helpers looked on in delight, one of our group noticed a half dozen golden trophies that adorned a case in a corner of the room.

“Are those awards for your amazing soba-making?” she innocently asked.

I translated and Tsuzuki-san blushed and looked down at the tatami mats, then back bashfully at me. “Actually, no,” she said slowly. “Those are for folk-singing. When I was younger, I entered many folk-singing competitions.” Then she scurried back into the kitchen.

The Art of Japanese Folk Song: An Unexpected Cultural Connection

As we were finishing our feast, I wandered back into the kitchen to tell her what an amazing experience she had given us and how grateful we all were for her and her companions’ generosity, energy, and spirit. I told her that this was one of our most special experiences in Japan and that we would always treasure it.

Then I looked at her. “Tsuzuki-san,” I said, “we would all really, really love to hear you sing a folk song. Would it be possible, would you be kind enough, to sing a song for us? We would be so grateful!”

“Really?” Tsuzuki-san said, her eyes widening. “You would really like to hear me sing?”

“Just a moment,” I said. I stepped back into the living-dining area and called for the attention of the group. “Excuse me, everyone, but would you like to hear Tsuzuki-san sing?” All eight erupted into cheers, whistles, and clapping.

I returned to the kitchen with a smile and said, “Yes, Tsuzuki-san, they would really like to hear you sing.”

“OK,” she said, blushing. Then she took off her apron, adjusted her hair with her still floured hands, and walked with a big smile back into the eating room.

Everyone applauded, iPhones were readied, then silence settled over the room.

Tsuzuki-san stood in front of us, cleared her throat, and said, “This is a song that women traditionally sing as they grind the buckwheat for soba, just as you did earlier today. It’s a song that encourages women to be strong, but also gentle and kind.”

She closed her eyes and seemed to gather all of her energy into her five-foot frame. Then she opened her mouth and the most extraordinary, plaintive, plangent melody emerged. Her voice was a wavering warble that seemed to ascend the hillsides, get lost in the high grasses and misty cedar boughs, and then return to our tatami-matted room. It was as clean and clear as the river we’d crossed on a vine bridge earlier that day, and it soared like the mountain breeze that had swayed the bridge.

Her song filled the room with centuries of hardscrabble existence, resilience, toil, determination, community. As she gently swayed back and forth, eyes closed, lost in her song, the sweet melody and poignant strains wrapped around each of us and took us with her, through time and space, to the very heart of this special place.

After a few minutes that seemed eternal and momentary at the same time, she stopped, opened her eyes, and realized with a start where she was. She looked at us all shyly, then everyone sprang to their feet and burst into a standing ovation, swelling the room with whoops and whistles.

“I was not expecting to do this,” she said to me, tears glistening in her eyes.

Without even thinking, I bent down and enfolded her in my arms. “Thank you, thank you for a gift we will never forget,” I said.

We looked at each other and smiled: A bridge was woven; a tradition was born.

Creating Lasting Traditions

Now, every spring, I lead a vanful of travelers along the winding road to Tsuzuki-san’s workshop-restaurant. We don aprons and kerchiefs, knead and slice and boil, laugh and feast and lose ourselves to something larger.

We honor and renew that tradition, reweaving a bridge threaded with soba, and song, and the transcending spirit of an Iya Valley treasure.