Two Angels in Anatolia

Sometimes the most poignant gifts of travel are the most unexpected, and sometimes innocence is the key that unlocks a transformative travel experience. This premise is at the heart of Lonely Planet’s engaging anthology An Innocent Abroad, which presents 35 tales of life-changing trips by acclaimed and emerging writers. In the coming months, Wanderlust will be presenting a series of excerpts from this collection, beginning with today’s poignant tale of fear and redemption on a rural road in Türkiye (formerly Turkey) written and illustrated by world-wandering writer and artist Candace Rose Rardon.

When I decided to walk the Evliya Çelebi Way, a 220-mile trail across northwest Türkiye, named after the 17th-century Ottoman traveler whose pilgrimage to Mecca it follows, I didn’t exactly stop and consider whether doing so as a woman on my own would be safe.

I did question if my decision not to purchase a pricey GPS in Istanbul beforehand was foolhardy – the authors of the only guidebook to the route had deemed the item “essential,” after all – but for the most part, there was little that gave me pause before embarking on the journey. Not the fact that my backpack tipped the scales at nearly half my own body weight; nor the fact that sleeping alone in a tent along a mountainous path might prove more frightening than fun; nor the fact that I spoke no Turkish and would be passing through remote villages where my chances of coming across anyone who spoke English were incredibly slim. In fact, my only real concern on the day I left Istanbul had been finding an appropriate pair of waterproof trousers to wear on the trail.

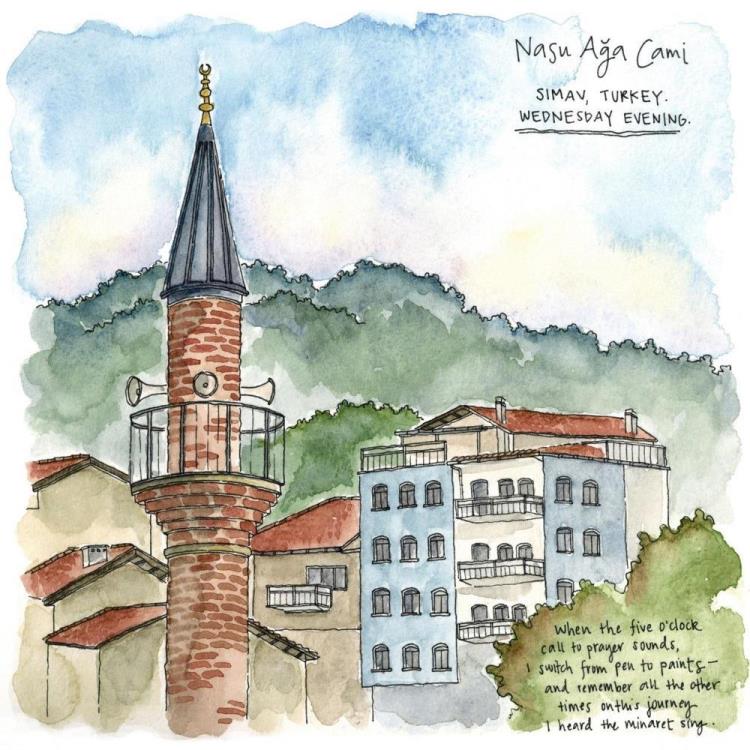

For the first three weeks, however, my time trekking through Anatolia was a brilliant success. I befriended farmers and shepherds, was invited to sleep in local families’ homes, listened to the call to prayer ring out across the olive groves and tomato fields, reveled in ruins over 2,000 years old, picked up dozens of new words in Turkish, and every day, grew a tiny bit closer to the route’s final destination of Simav. And yes, the waterproof pants had held up remarkably well against all manner of rain, wind, mud, stream crossings, bushwhacking, forest navigating, and encounters with curious goats.

The Guys of Gürlek

One Sunday morning, my twentieth day on the Evliya Çelebi Way and just two days from Simav, I arrived in the village of Gürlek. There wasn’t much to distinguish it from the scores of villages I had already passed through. A small sign at the entrance to the town read Hoş Geldiniz – one of the first phrases I’d learned, Turkish for “welcome”; all the narrow dusty streets led to a silver-domed mosque with two minarets, the sapphire tiles on their pinnacles gleaming in the bright sunlight; and when I came to the village kahve, or teahouse, I was quickly ushered inside by several gray-haired men for a steaming cup of çay.

Like the countless other villagers I’d met during the trek, they laughed away any attempt to leave a lira or two in the saucer of my tulip-shaped teacup.

By the time I left Gürlek, my belly was warm from tea and my heart from yet another gesture of kindness from strangers. I had heard stories about Turkish hospitality before arriving in the country, but it had been altogether different – and profoundly humbling – to experience it for myself, time after time. So caught up was I in my reverie, reflecting over the generosity I had been shown on my journey thus far, that it took me longer than it should have to notice two young men following me out of the village.

They seemed to be in their early 20s, and I recognized one of them from the kahve. He had offered to accompany me over a mountain, claiming it was a shorter way than the stabilized road I planned to take, but I’d declined. Apparently he hadn’t accepted my answer. No matter how fast I walked, they held my pace. This went on for fifteen minutes, until I turned around and thought I might as well confront them head-on. I planted both feet in the ground, Superwoman-style, and held my walking stick as though it were more than just a long branch I’d found on day eight and carried with me ever since.

“What do you want?” I asked, hoping I looked far more formidable than I felt.

“Why are you following me?”

Sly grins broke out across their faces. “We go to our fields.”

I couldn’t argue with this, but still I was shaken. I passed a small farmhouse and saw an older couple sitting outside. We waved hello to each other, and though I contemplated stopping and waiting for the guys to pass, I kept going.

Roadside Assistance

Minutes later, a car pulled up and lowered its window. It was the same couple, offering me a ride to the next village of Üçbaş, some two hours away on foot. This wasn’t the first time I had been taken as an unsuccessful hitchhiker. People were constantly slowing down beside me, and I was forever having to tell them that I was gezmeye gitmek, or taking a walk. A very long walk, you might say.

I didn’t know if this couple was merely being kind, or if they had seen the guys on my trail and taken it upon themselves to convey me safely to Üçbaş. As we talked, I watched the pair come into view and turn down a side road between fields. I watched them until they crouched to the ground and disappeared out of sight. I thanked the couple, explained that if at all possible, I wanted to walk every mile to Simav, and continued on the path. A little voice inside me asked if I was being stubborn or just stupid.

After a few minutes, I glanced behind me and saw the men cutting across the field, once again heading in my direction. That’s when my annoyance turned to fear.

It isn’t something I experience often in my day-to-day existence as a writer and artist, sitting at my desk or sketching on-location. But here there was no mistaking it – the pulse-quickening, blood-thickening instinctual feeling of fear, pumping a steady surge of adrenaline into every cell in my body. I could feel it at the tips of my fingers, coursing through my veins, making every hair stand on its unwashed end. The last time I’d felt fear so physically was at the edge of the Nevis Highware Platform in New Zealand, as I was about to throw myself off the country’s highest bungy jump. But there had been a safety cord around my ankles then, and despite official warnings and waivers, I had every reason to believe I would be just fine.

There was no such assurance on the road out of Gürlek. Again I had thrown myself off the edge of a safe life into the unknown, and for three weeks, by the grace of God or chance or some uncanny combination of the two, I had stayed out of harm’s way. The villagers I met never failed to warn me of the dangers I faced – of dogs and bears, wolves and wild pigs, and those they called “bad people.” The first question they always asked was korku? Was I afraid? Every time, I blithely assured them I was not, that I had met nothing but good people, but deep inside me that same voice spoke – was I trusting or just naïve?

I couldn’t help but think that maybe my luck had at last run out. Had the limits of my innocent faith in the world and its ability to take care of me been stretched too far? I was alone on a deserted road in rural Türkiye, I hadn’t checked in with my family for days, and I didn’t even know if the road I’d taken was the one I needed to be on. Behind me were two guys whose intentions for following me were anything but clear. Did they have their eyes set on the expensive camera swinging from my neck? Perhaps the wallet one guy had seen me take out of my backpack in the kahve? Or was their objective much darker? As a woman who usually travels alone, I am all too used to conjuring up a hundred worst-case scenarios in my mind.

I didn’t want to let the guys know I was worried, so I forced myself to keep my gaze fixed straight ahead. I walked as fast as I could until it would be considered running. I came to a stretch in the road where it partially bent back on itself, and when I crossed a short bridge that was sheltered by oak trees, I cast a quick glance behind me through the branches.

Not only were the guys still there, now they were the ones running.

And so I did what I’d done a few other times on the path when things were getting desperate. I stopped walking, looked up at the big blue dome of a sky stretching out above me, and said three words: “Please help me.”

What I had hoped would materialize was another car – preferably one aiming for Üçbaş – but what I couldn’t have known to pray for were two middle-aged men suddenly emerging from the forest, walking sticks clicking in time with their stride, ambling towards my path as though this were a perfectly normal place to be on a Sunday morning stroll.

“Merhaba!” I called out to them. Hello!

I waited for them to reach the road, and was relieved when they said I was heading in the right direction. We said goodbye and went our separate ways – me to Üçbaş, they to Gürlek. I felt some of the stress begin to fall away, knowing there was now a buffer between the two guys and me. I was even wondering what the guys might say if they encountered the men when I heard a loud voice booming from above.

I looked towards the top of the bluff and saw it was the same two men. I didn’t understand what they were saying, but again, I stood there while they made their way down the road. And when they got to where I was, they carried on walking with me as though we hadn’t just parted five minutes earlier. I didn’t get it. Had they, like the couple from before, come across the guys and realized I might need help? Or had they simply discussed the situation between themselves – this blond-haired, fair-skinned female foreigner walking on her own – and decided she could use some company to the next town?

Walking With Angels

They walked with me for an hour, and as we walked, I got to know them. Their names were Ismail and Murat, and from what I could tell, they had been friends since they were kids. Ismail was 62 with salt-and-pepper hair and a matching mustache. Murat was five years younger and several inches shorter. They were each dressed in the standard male villager’s outfit – button-down collared shirt, pressed pants (or jeans, in Ismail’s case), and a blazer with patches on the elbows. Although they both grew up in Gürlek, Ismail said he now lived in the seaside city of İzmir, and was back for two weeks seeing family and friends.

Walking with Ismail and Murat, I’d never felt safer on the trail. In an instant, the pendulum of my fear had swung to the other side. I could relax and finally notice how beautiful the countryside around us was. The open rolling hills, which before had seemed almost too open, too quiet, were once again inspiring, their slopes a pastoral patchwork of autumn’s glory.

The two men laughed a lot, and I imagined it to be the laugh of old friends ribbing each other. They introduced me to a few shepherds we passed, and every so often, Murat would stop and dig around in the soil along the road with his walking stick. I didn’t know what he was looking for until at one point, he kicked away dirt from what appeared to be a round white stone, reached down, and wrenched from the ground the largest mushroom I had ever seen. He carried it with him proudly, his walking stick in one hand and the mushroom held high in the other. It took Ismail 45 minutes to remember he had a plastic grocery bag in the front pocket of his blazer, which he then ceremoniously fluffed open and gave to Murat to transport his prize in.

Soon after Üçbaş came into sight on the horizon, we arrived at a junction. I would go right, the men would go left and return to Gürlek. I wanted to hug them, but settled for modest handshakes. With each man, I placed both my hands on his and tried to communicate – through osmosis if not by words – just how much I appreciated their company, just how much of a gift and a godsend it had been. I’m not sure they understood, for when they walked away, I only saw them shake their heads and mutter, “Maşallah, maşallah.”

God has willed it. God has willed it.

I will always wonder why Ismail and Murat turned around that morning, why they decided to go two hours out of their way to walk with me. I will always wonder what would have happened if they hadn’t.

One of the things I’ve learned in my wanderings is that travel demands a certain amount of trust from us. This trust may sometimes seem naïve, but if we were to let our fear of fear have its way, we would never set off on a trip – indeed, we might never leave our homes. For as soon as we step out the door, off the edge, and open ourselves to the world, we also open ourselves to the possibility that things may not always be safe.

But I have found the rewards the world offers us are almost always worth the risk. As they were on that Sunday morning in Anatolia, when two angels walked with me on the Evliya Çelebi Way.

“For truly we are all angels temporarily hiding as humans.”

– Brian L. Weiss

*****

Candace Rose Rardon is a writer and artist whose stories and sketches have appeared on numerous sites, including BBC Travel, AOL Travel, World Hum, Gadling, and National Geographic’s Intelligent Travel blog. A serendipitous invitation to move to London after her college graduation sparked a six-year love affair with the world—one that has taken her from a black pearl farm in the South Pacific, to a 2,000-mile rickshaw run across India, to a remote village of nomadic sea gypsies in Thailand. Originally from the state of Virginia, Candace has also lived in England, New Zealand, and on a rural island in Canada. This extract is adapted from An Innocent Abroad, © Lonely Planet 2014. RRP: $15.99. www.lonelyplanet.com.