Travels with Suna

Note: Lonely Planet has just published Better Than Fiction 2, a compelling collection of true travel stories written by acclaimed fiction writers. We are pleased to excerpt the story below, by Shirley Streshinsky, about a traveling companion who transformed her life. Streshinsky is the author of four historical novels and four works of non-fiction, as well as numerous travel stories for such publications as the San Francisco Examiner, Condé Nast Traveler, and Travel + Leisure. Her most recent book, with historian Patricia Klaus, is the biography An Atomic Love Story: The Extraordinary Women in Robert Oppenheimer’s Life.

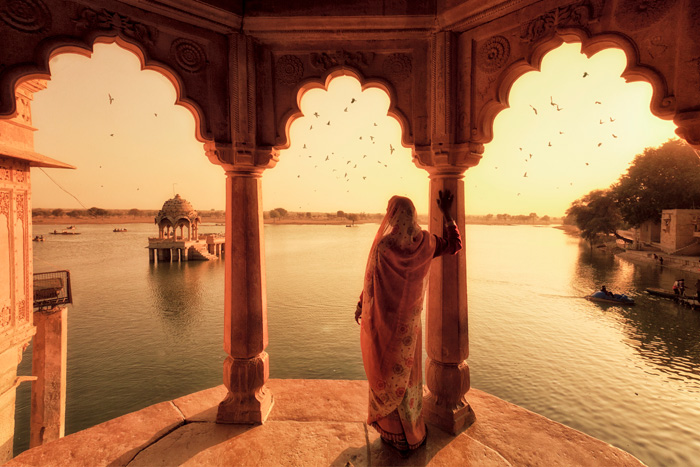

The flight from Calcutta was crowded; the sari-clad woman named Suna took a seat up front, while I pushed on down the aisle and found a window seat. My view of India from the air included the Boeing 737’s wing and engine. We were on our way to Bhubaneswar, a city of temples, but would be making a stop at some small outpost in between. After about half an hour, we started our descent.

I watched as the ground came up to meet us, and glanced around to see if anyone else was concerned with what seemed to me to be much too rapid a descent. No one was. I pulled my seat belt tight and took a deep breath. Then I looked out the window just in time to see the whole back of the engine fall away. Dear God, we’re going to crash. I wanted to scream but I couldn’t breathe. I felt myself go numb, covered my eyes, and waited for the explosion.

We touched down, bounced once or twice, then rolled to a stop. Passengers busied themselves pulling out bags crammed in overhead bins.

“The engine,” I croaked to one of the attendants, “the engine, part of it fell off.” The young woman pressed her hands together, fingers up, said, “Namaste,” and turned away. I had to do something. I could not get back on this plane without alerting someone to the problem; it would be irresponsible. I waved to Suna. She would know what to do, I was certain of it. I had sat next to her on one of the bus trips that our group had taken; she had grown up in India. She exuded calm.

“We must go to the pilot and tell him what you saw,” she said. Action, yes. Without hesitation, with perfect equanimity.

The pilot came out of the cockpit along with the co-pilot. Suna spoke to them; they nodded and suggested we follow them onto the tarmac to inspect the engine.

“You see?” the pilot asked. I didn’t see. I looked down the runway, which was surprisingly short, but there was no evidence of the missing piece of engine.

“Not to worry,” the co-pilot assured me, but he didn’t say why.

“Are you certain?” I asked.

“I am certain,” he murmured, god-like. Later, Suna told me he mentioned that English women regularly reported engines falling off. She didn’t know what to make of it and neither did I, so we continued on to the city of temples.

Back home in California, the reporter in me pushed for answers, so I called Boeing to ask what exactly had happened with that errant engine. They obliged: On older versions of the 737 the back of the engine acts as a thrust reverser; the clamshell design allows one part to slide down during landing. It is part of the braking system, often used when a landing strip is short and requires a fast landing. When I covered my eyes to wait for eternity, I failed to see the clamshell slide back up and lock into place.

I was embarrassed, yes, but mainly what I felt at the time was gratitude to Suna Kanga for being willing to risk standing up with someone who was making a fool of herself.

Travel Writer

More than three decades later, I wince when I think about how close I came to missing that meeting with Suna altogether, and so never discovering the gate she would open for me.

The year was 1981, and I was at a loss to know why the government of India would invite me on a press trip and I did not plan to accept. My family rebelled. Not just my photojournalist husband, who routinely traveled the world on assignments, but our 13-year-old son and daughter as well. You have to go, they chimed in.What could be more exciting? “But I’d miss your 11th birthday,” I told my daughter. She said I could bring her presents.

I didn’t try to explain to the government of India that I was not a travel writer, that I wrote articles for magazines about people like a Navy nurse who had been court martialed for protesting the Vietnam War; about the Berkeley schools’ radical new integration plan; about the killing of a young white bus driver in the riots after Martin Luther King’s assassination. I had just published my first historical novel and was about to begin another. Still, my only foray outside of the US had been to London, to interview two survivors of the Holocaust. I tended to write about what was wrong with the world; it seemed to me that travel writing by its nature was expected to cover much that is right, to pay more attention to pleasure than to problems. I asked myself how I could possibly do that in India, of all places. The answer was: The only way to know is to go.

India

When I returned, I wrote a story for a travel magazine. It was titled Interlude in India, and it began: “It had not occurred to me that I would go to India, ever. The Taj Mahal floated in my mind like some shimmering mirage, cold white and dream marble… The India of my mental landscape was monochromatic, brown as the river Ganges, sere and dusty and filled with too many people, too many poor. I didn’t realize how vague was my notion of what I was about to encounter… I am not a traveler by inclination; I should not have come.

“The days between New Delhi and Calcutta were spent touring Hindu temples and second-century Jain caves, traveling to ancient forts and holy ghats on the Ganges. Our guides delivered long, sonorous lectures – stories about ancient struggles between the elephant and the crocodile, good and evil, about Mogul emperors and Sikh gurus. In their lyric, embroidered English, the well-versed guides would chant out interminable tales, explaining all the subtle variations in all the myriad religions, until finally I tuned out the words and listened only to the cadence of their voices. And that is when I began to hear India.

“I would wake before dawn in my hotel room and lie quietly, waiting for the light. Then, through an air vent came the softest imaginable chanting, drifting up through the air-conditioning system, lulling and beautiful and strange: the morning prayers. In the distance I could see a mosque outlined against the gathering pink of the sunrise. After a while the smell of smoke would drift up and into the room, smoke from a thousand braziers on the street, lit to cook the morning meals.

“In India all of life can be viewed on the street – cooking and bathing, hair cutting and sewing and the patting of cow dung into small round cakes to be dried in the sun and used for fuel. In the streets, movement is perpetual. My monochromatic India, all brown and dusty green, was actually alive with movement and color – outrageous, amazing splashes of cerise and jade green and saffron yellow, glittering with silver and gold.

“…At the Harmandir Sikh temple people crowded about, curious, as we washed our feet in a trough before covering our heads with saffron-colored scarves so we could enter the temple, where we were taken on a tour which included a visit to the common kitchen where food for a thousand is prepared each day. I don’t know what I expected, certainly not what I saw. Two shadowy stone rooms, dungeon-like, had only a few shafts of light penetrating through narrow windows. Open fires blazed in trenches in the floor. The heat was choking, yet women and children squatted, hour after hour, patting out flat bread on the stone floors. I stood in the suffocating heat and watched a tiny girl, no more than five, methodically slap the bread rounds with a splash of water.

“When I came back into the full sun of the plaza, something lurched inside me. I was walking next to a Belgian journalist named Andre, and I was surprised to hear myself tell him, “I feel like crying, but I’m afraid if I start I won’t be able to stop.” He looked at me for a long moment, then he said, ‘Either you leave India and are so repulsed that you never want to return, or you will have to come back.’ After his first trip, he told me, he spent two years reading everything he could find about India. He comes back every chance he gets, he explained, ‘to try to understand.’

“In Calcutta, the women carrying babies high on their breasts would walk alongside me, chanting a peculiar incantation which might have been memorized for Western women: ‘Oh Mommie,’ they droned. ‘Oh baksheesh, oh baby, no papa, oh Mommie.’ But I did not give them baksheesh, and I would not cry for them. If you weep your way through India, if you cannot see beyond the squalor, you will miss the grace and the beauty and the promise.

“…From a distance it looks like all the photographs you have ever seen: floating in space, heat waves diffusing its focus. It is not until you pass through the Jilo Khana, the red sandstone gateway, that you really see it: The central tomb of the Begum Mumtaz-i-Mahal, white marble, soaring and brilliant in the midday sun. You run your fingertips over the traceries and arabesques formed by semi-precious stones inlaid in marble. You shade your eyes and peer up at one of the towers, glaring white against a blue sky, a remnant of a past only dimly understood, as well as an astonishing measure of possibilities for this crowded subcontinent.”

Suna

It was easier to leave India than to return home. Now that I had seen the slums of Mumbai and the beauty of the Taj Mahal, I understood my massive failure of imagination. I had written: “I am not a traveler by inclination; I should not have come.” India taught me that I had no choice, that I had to find a way to experience the larger world.

On that 1981 press trip, I learned that Suna was the journalist representing Singapore, where she lived with her husband, Rusi, a pilot for Singapore Airlines, and their two teenagers. I watched Suna navigate comfortably, both within the international group of writers and in the chaos that was India at large. In Suna’s world, everyone got the benefit of the doubt; no one was beyond redemption. There was something completely guileless about her. She could also be formidable, as I was to discover. And she was prolific; her stories appeared in magazines and newspapers in Singapore, Hong Kong, and India.

As it happens, her daughter was considering a college near my home in Northern California. When the family came to check out schools that summer, I invited them to dinner. In the following years, both Kanga kids would choose West Coast colleges, and both would be in and out of our house. Over time, my husband, Ted, would perform the wedding ceremonies for both (using his Internet credentials) and our children would become friends. I ended up recording the story of the “crash” of the Boeing 737 for a travel program on National Public Radio; Suna included it on a tape of stories she put together for her grandchildren, and it became their bedtime story.

*****

Eventually our families would blend to include extended family and good friends, but at first it was just Suna and me traveling on our own. She was easy in the world in a way that I was not, and she made me feel comfortable; in effect, she became my gatekeeper, a conduit into a wider world.

Our first foray together was to Hong Kong, where we signed on to one of the small tours into mainland China, to Guangzhou. It was Suna’s choice because it included a visit to Shamian Island, once a foreign enclave.

When we arrived, our guide told us that Shamian Island had been removed from the tour. Suna objected quickly without raising her voice. The guide said there was nothing he could do about it. Her face took on a look that I would come to recognize: total determination. Quietly, purposefully, she found one after another reason to bring up the question of Shamian Island. The guide took me aside to ask why my friend was being so insistent.

“She was born there,” I told him. “Her father was a businessman, and he was President of the Indian Association. During the Japanese Occupation, he was falsely accused of spying for the British. He was arrested and tortured, and he died soon after. On Shamian Island.”

The Chinese guide grew quiet. “I see,” he said, “it is a matter of the heart. I myself will take you there.” And he did. Late that afternoon, I followed Suna as she walked around the gray European-style mansions where the foreign business community had been confined in the years before World War II. Suna had childhood memories of the house, of a bridge over the river where she used to play. The guide and I trailed after her, until she found the once elegant house where she lived with her family and younger sister. It now housed eight families. We invited our guide to tea at a nearby high-rise hotel recently built to attract tourists. He was delighted; Chinese were welcome there only if they were with registered guests … or two foreign women, it would seem.

*****

After that, we found reasons to explore other destinations in various parts of the world, sometimes with effects that would play well in an action movie. We were chased out of Puerto Rico by an impending hurricane; the first available flight landed us in New York City at midnight, in a downpour and without luggage. In Goa, the only available driver had spent the afternoon drinking the local brand of white lightning. In Salt Lake City we had to take shelter in a small opening tucked under the Mormon Tabernacle when a tornado ripped through.

In Bangkok I was researching a novel that involved drug running, and I hoped to get a look into one of the city’s prisons so I could write convincingly. Suna suggested we ask the hotel’s concierge. Never blinking, he called over a cabdriver who studied us for a long minute, then suddenly smiled and said, ‘You ladies want to go to the prison store for shopping.’ He managed to maneuver us into an area where prisoners could meet visitors, all of us guarded by soldiers with rifles.

Yet it is other, smaller moments that linger in my memory, like a sultry day in a cab in Mumbai, stalled in traffic, when a beggar boy suddenly thrust his hand through my open window. I happened to be carrying an orange, and plopped it into his palm. He took it and started to turn away when Suna called him back to ask, “What do you say to Auntie?” A boyish smile appeared, and he looked at me and said, “Thank you, Auntie.”

Wherever we went, Suna’s approach was simply to slow down and settle in, to move through exotic places and absorb the culture of a people without making judgments on how they lived. On all our journeys, she saw what was right without denying all that was wrong.

*****

After Rusi retired, he and Suna became a writer-photographer team, and set out on a series of wilderness adventures. Suna added blue jeans and flannel shirts to her wardrobe and they signed on for safaris, river rafting, mountain climbing; they explored the Amazon, the Nile, and the Danube; climbed on the train to Lhasa in Tibet, trekked to Bhutan’s Tiger’s Nest temple. They gave me a copy of the lavish coffee table book they produced together titled Journey through Colombo: A Pictorial Guide to the Gateway of Heavenly Sri Lanka.

During this period, Ted and I met them in Spain, and the four of us explored the White Villages of the south. One day we took a wrong turn and came upon a small, off-the-track village, one which seemed perfect to return to, maybe spend a month or two together, long enough to settle in.

We never did. Ted died in 2003; some months after, I went to India to be coddled and comforted by what seemed the whole Kanga clan, sisters and cousins and squadrons of relatives and friends.

For the past several years I have stayed closer to home, working with a historian friend on a biography titled An Atomic Love Story: The Extraordinary Women in Robert Oppenheimer’s Life. Suna and Rusi kept up by phone and email, and there were quick visits when they came to the States to see their children. We never let too much time lapse between conversations.

A few weeks after An Atomic Love Story was published, Suna and Rusi called to say they would be coming for a short visit. Happily, they were arriving the day before we were to give a reading at a bookstore, with a party afterwards at a friend’s house. All my kids happened to turn up, as well as many friends the Kangas already knew. The afternoon was sunny and warm, there was standing room only at the bookstore, the party was in a house worthy of those Suna used to cover for a column she wrote called Beautiful Homes. I have photos of us, taken after most of the guests had left, sitting in a wide circle, my daughter tucked on the arm of the big easy chair Rusi was in. My two sons shared a large bench, Suna and two of my friends were on one sofa. I do not remember the conversation, only the laughter and sense of ease.

The evening before they were to leave, the three of us were sitting at my kitchen table with cups of tea. Usually there would be a conversation about a next trip, but it didn’t come up. I remember Suna asking if I’d heard from her daughter, Nazneen. I said I hadn’t, but suddenly I could see how weary Suna seemed, and since they had a long travel day ahead of them, I suggested they turn in.

The next morning I saw them to the car, hugged them both goodbye, kissed Suna a second time. I watched until the car turned the corner and was gone, and then I cried.

*****

Fifteen months later, on the 10th of February, 2015, Suna’s son, Cyrus, was in town and came to dinner, as he usually did. By then, I knew that Suna had been diagnosed with leukemia three years earlier, and that she had made the decision to reject chemotherapy or any of the other therapies that could prolong her life. She wanted to live fully for the time left to her, she did not want to be treated like an invalid, and so had insisted that only her immediate family know. We were in the kitchen when the call came from Rusi in Singapore. Suna was failing, they were taking her to the hospital. She died five days later, as she had lived: resolute, positive.

The Kangas are Parsis, a religious denomination that came to India from Iran; their prophet is Zoroaster. Suna’s final assignment had been a grant from the National Heritage Board of Singapore to write a book about the Parsis of Singapore, their history, customs, culture, and cuisine. She and I had discussed the research it would take, the excitement of dealing with a historic subject; we spoke of the pleasures of writing non-fiction, the satisfaction of being able to add to a body of knowledge. She worked on the book steadily, and was able to finish half. Parsi friends will complete it in her honor.

My travels with Suna are over; we won’t be meeting in Rome or Paris, in Hawaii, Hong Kong, or Kuala Lumpur. There will be no more misadventures, no fallen airplane engines in India or random tornadoes in Utah, stories that our children now tell their children. Suna and I covered a wide swath of the world together and in the process we caught our families in a kind of charmed net that pulled us all together, and holds us, with Suna locked in our memories, secure.

And yet, and yet… I cannot quite believe that one day soon she won’t call to tell me that the trip is on, that I should not forget my bathing costume. She would remind me, I am certain, that the gate remains open, just the way she left it.

#####

Reproduced with permission from Better Than Fiction 2, 1st edition, edited by Don George, with contributions by M.J. Hyland, Francine Prose, et al. Copyright © 2015 Lonely Planet.

Purchase this book here.