The Life-Changing Magic of the African Safari: A Travel Story

African safaris confer a magic all their own. The beginning of the spell is simply the gift of being a guest in the seemingly boundless home of so many magnificent creatures. You quickly realize how small and insignificant you are in that vast wild world, and this realization morphs into gratitude for the infinite wonders of life in the bush.

For me, most prominent among these wonders are the countryside, the wildlife, and the people.

I first visited Africa in 1976 at the end of a post-university year abroad in Greece. Two of the students at Athens College, where I was teaching, lived in Tanzania, and their parents invited me and a fellow teacher to visit them. On that footloose, youthful visit, we climbed Mount Kilimanjaro on a whim, and then they took us on a safari deep into the heart of the country.

One of my first impressions on that safari was the magic of the sounds and sights of the bush. As I wrote in my journal:

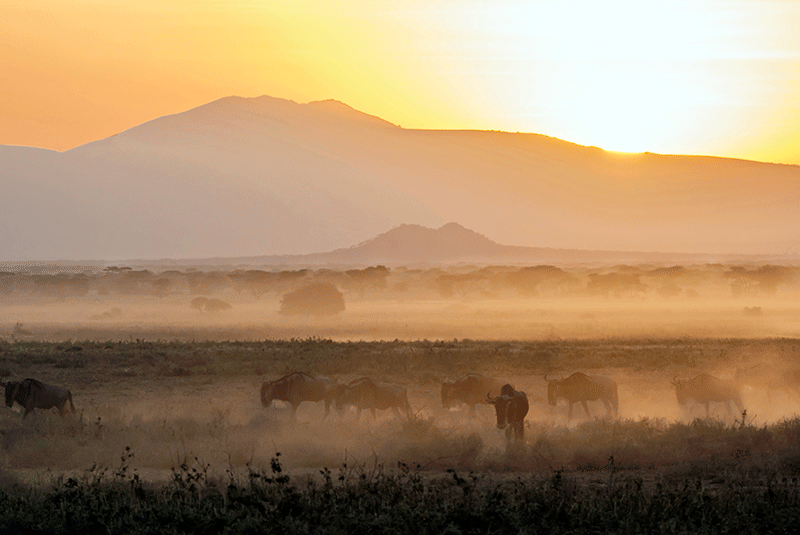

We departed camp at 4:30. The country was alive with sounds: the deep-throated croak of frogs, the shrill incessant tring of cheepers, the haunting hollow warbles of birds announcing dawn. For a half hour we drove into the bush through the elephant grass, bumping over potholes and rocks, around fluttering acacia and jagged thorn tree, and past the thatched-roof huts of awaking workers.

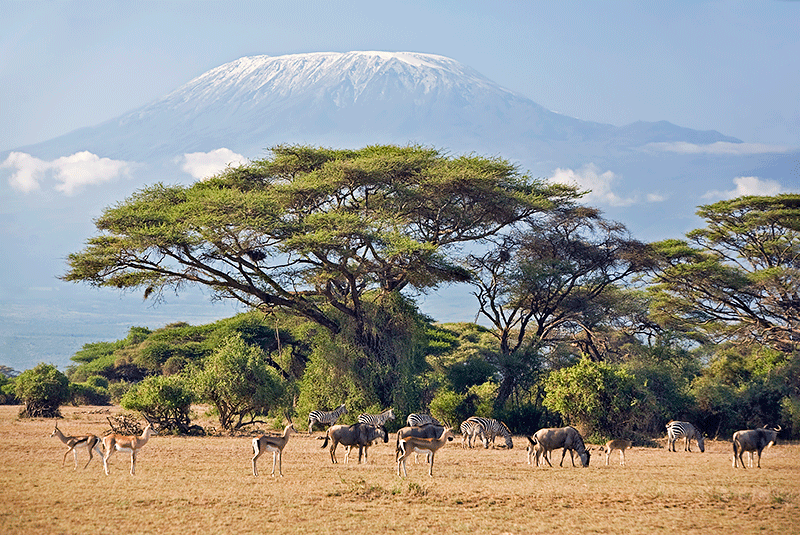

The first lines of dawn were just beginning to color the eastern sky. Hills and trees began to take depth and shade, and the crinkle in the air seemed to soften. We drove for two hours through the East African countryside: brown and green savannah dotted with gigantic anthills like sandcastles, some eight feet high; spindly, silver-green acacia like giant bonsai; intricate white-thonged thorn trees; squat, massive-trunked baobabs; and dark green hills on the horizon, hovered over by stretched-cotton clouds and covered with an even blue swatch of sky that seemed to stretch beyond the hills and out of sight. I have never seen such a landscape, never moved through such a world, before.

That exotic landscape began to cast a seductive spell, which only deepened as afternoon turned to dusk:

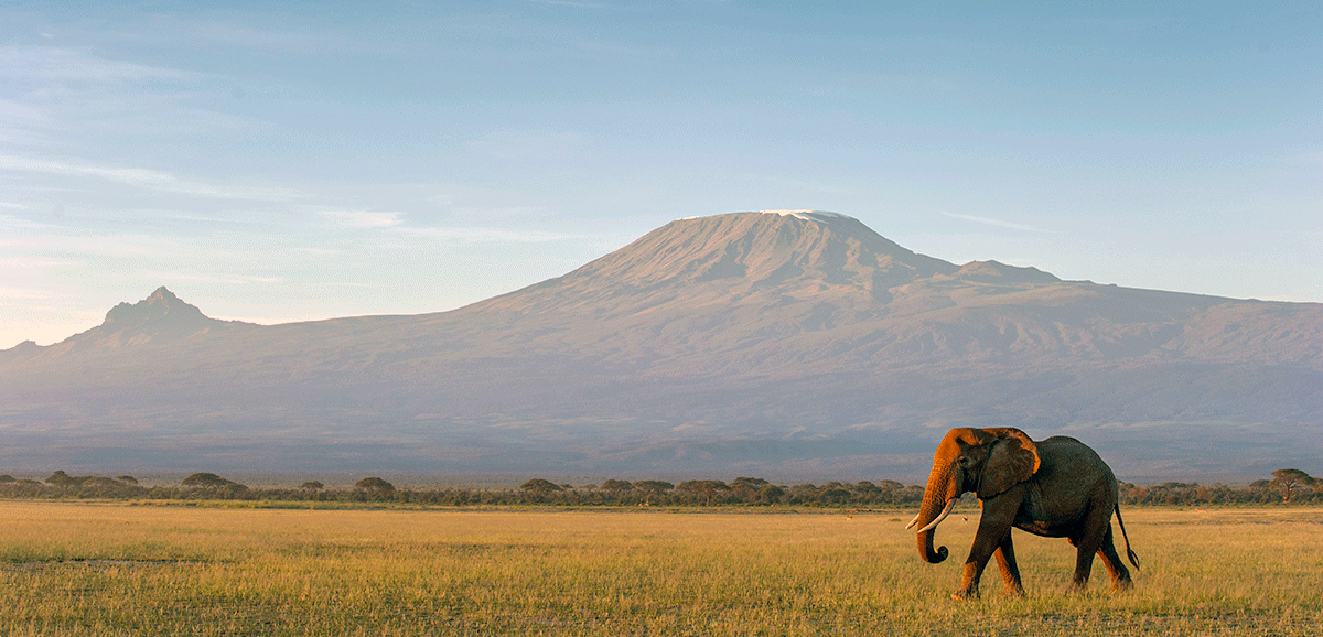

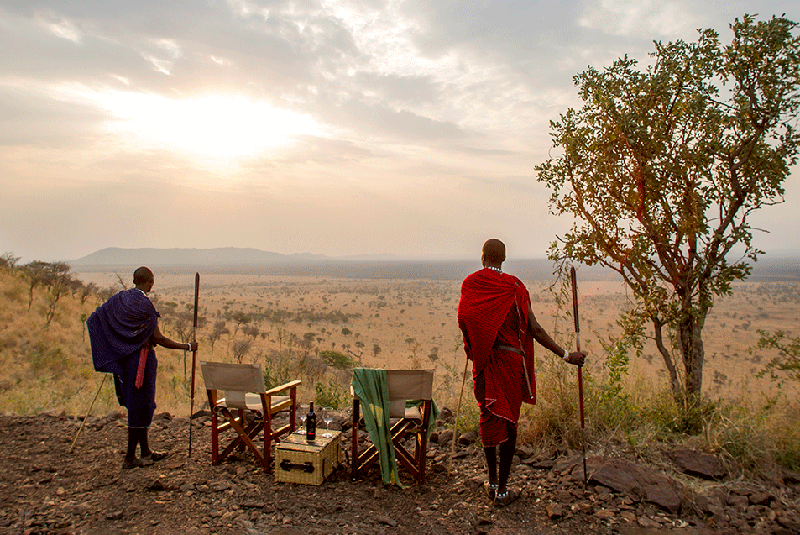

When we set out in the late afternoon, the sun was half submerged and bathed the land in an orange light that gradually turned to red, then blue, then purple. I sat on the Land Rover roof as we rode. The air was cool and fresh with the approaching night, creepers echoed from the high grass, and the plains exuded the full scent of baked dirt and dry brush. We passed herds of wildebeest that seemed to carpet the savannah, and gazelle and zebra loping in the distance. The sunset washed the western sky in shades of violet, saffron, rose, and chartreuse, while stars engraved the indigo of the east.

As I leaned back on the roof, I saw those stars as they had never appeared to me before, isolated travelers in the vast vault of the sky roving an immense and uncharted universe just as we roamed this wild and expensive land I had never known. For a moment the wind and the savanna smell and the bush shapes seemed to merge in roof and star, and past and future seemed to concentrate in this present of unceasing movement, this fixed dance of breath and angle and light. Lying on the vault of the Land Rover, I left a part of myself to that moment on the African plain, and gained in its place the piece of a design not to be sought nor defined, but only lived.

Just over three decades later, in 2007, I returned to go on safari again in Tanzania and Kenya. The magic I’d felt in 1976 asserted itself immediately, and powerfully, in two primal dramas I and my traveling companions witnessed as soon as we left camp. Here’s how I described them in my journal:

We’d been driving for about 15 minutes when we came upon a swamp. Lewela, our safari director, suddenly pointed to the far shore, “Look! Over there!” Four heads swiveled. Three feet from the water’s edge, a lioness was lying next to the bloody half-carcass of a zebra, the remains of the pride’s dinner.

Another lioness was lying down about 20 feet away, sated, so exhausted from the effort of eating and digesting that we could hear her labored panting and see the bellows of her tawny body moving in and out. Soon a great drama began to unfold. First wiry jackals cautiously approached the carcass, smelling the air, anxious in their hunger, waiting for an opening when they could dash in and make off with some lunch. Then two hyena came loping across the savannah, eyeing the lions, warily working their roundabout way toward the glistening kill.

For a long time the lioness let them approach, head on paws, eyes closed, seemingly oblivious. Then she slowly raised herself, turned, and began a purposeful stride in the direction of the jackals and hyenas. For a few seconds, the world stopped. Then they scooted away, followed closely by the lioness’s eye. When they had retreated sufficiently far, she returned to her resting place and curled up again, right next to the carcass. One of the jackals emitted a plaintive yelp. Lunch would have to wait.

Another drama began to play out in the swamp. The wildebeest and zebras started to cross, entering the water in a straggling line, following the leader across the depths toward the opposite shore. Suddenly, about a third of the way into the swamp, one of the wildebeests began to flail wildly. It had strayed off the path into deeper waters and bucked in terror for a few seconds before it found its footing and splash-charged into shallower waters and onto the far bank. “During the Great Migration a lot of wildebeest die this way,” Lewela said. “Either they drown or they get separated from the herd and become easy prey. The lions wait by the rivers like they’re at a buffet.”

As he spoke, the next wildebeest in line hesitated, confused, then looked around, snorted and galloped back onto the land he’d just left. The one behind him stood still for a second, then belligerently wheeled around and followed him back. Soon the entire line of wildebeest and zebra had beaten a retreat onto land, and the animals grazed and gazed placidly, now separated by the water, as if nothing had happened.

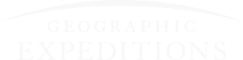

In the foreground a flock of long-beaked, white-winged great white pelicans erupted as one into the sky, swerving over the sweeping brown-golden grass-plains and toward the line of hazy green-purple hills beyond. Acacia trees thrust their thorny branches into the sky, and giraffe, elephant, and Cape buffalo materialized in the distance. The smell of fresh dung carried on the breeze, mixing with the dry dusty earthy smell of the land. And Mount Kilimanjaro brooded over it all, massing in the clouds. Africa!

On that return safari, as on my earlier one, encounters with wildlife bestowed many life-expanding moments. One of the most spellbinding was this unexpected connection with a behemoth of the bush:

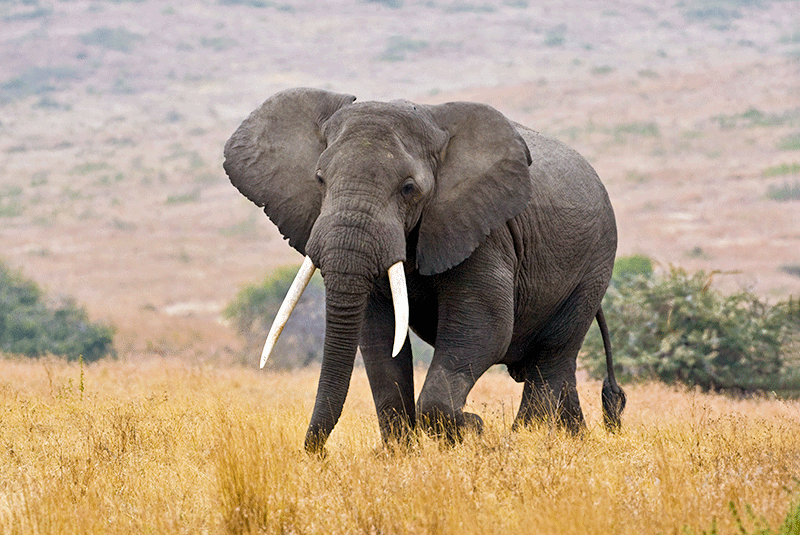

As the rising sun was just beginning to streak the sky, we hopped into a van and set out. Bouncing on dirt tracks through the dry brown savannah, we soon spotted a herd of elephants in the distance. As we approached, Lewela said, “They’re probably walking toward a waterhole for their own version of morning tea.”

The elephants’ path paralleled the dirt road we were on, and we were able to drive alongside them for about ten minutes. Then the lead elephant veered to the right, directly onto our road. We stopped and watched in awe as a parade of elephants lumbered unconcernedly in front of us, less than 15 feet from our van.

There were twelve in all, ranging from mature adults nearly twice the size of our van, with two-foot-long tusks, to babies about as tall as a bicycle. They plodded slowly, deliberately, delicately across, a surprising combination of girth and grace, then plunged unhesitatingly into the dense tangle of trees and brush on the other side of the road.

Immediately the air rang with the sounds of tearing and scraping as they broke and uprooted their breakfast, grabbing great trunksful of branches and bushes and curling them into their mouths, where they methodically chewed them.

Suddenly the next to last elephant in the road-crossing parade stopped and turned toward us. Ears extended, tusks pointing our way, eyes staring straight at us, he ponderously maneuvered his tree-sized legs so that he faced us squarely. “Don’t worry,” Lewela whispered, “he’s just curious about us. He’s checking us out.”

For an electrifying moment, we stared at each other, and rather than fear, I found myself falling under the spell of the elephant. There was something so gracious, dignified, and wise about him. With his big round eyes curiously, peacefully staring, his Dumbo ears ever so gently flapping, his foot-long tusks just starting to curl, and his tail swishing, he seemed a big gray embodiment of curiosity and self-assurance combined.

We held our breaths and I felt a primordial gut-tug, like some spirit-understanding was leaping from me to the elephant and from the elephant to me. An inexplicable, irrefutable connection was fused, then the enormous tree-legs started to slowly turn, heroically bearing that wrinkled gray bulk, and the elephant slowly shifted course, heavy foot-step by heavy foot-step, and ambled off into the brush.

Encounters with the people of East Africa have conferred another kind of life-expanding magic, as on this memorable afternoon in 2007:

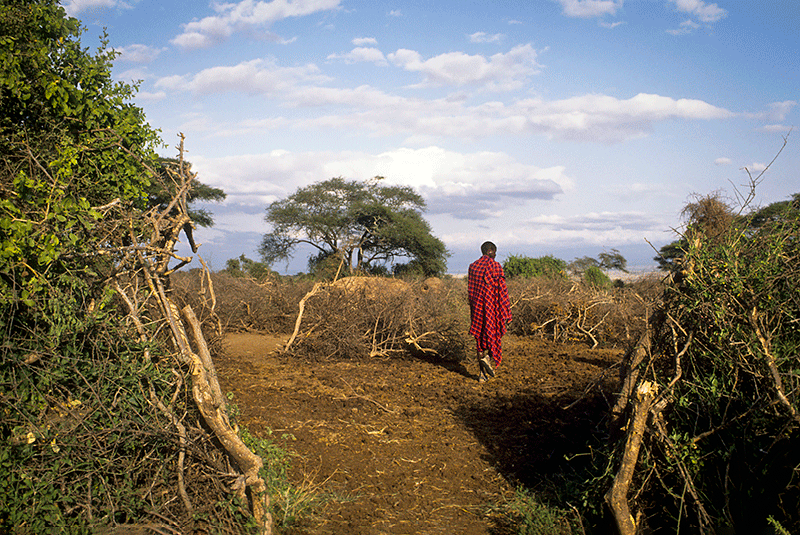

One day a local Maasai teacher, Andrew, brought us to his village. When we reached the village, Andrew showed us how to enter through a break in the encircling fence of thorny acacia. “Four families live in his village,” he said, “and there is one entrance for each family.”

The village consisted of a dozen huts, each made of mud laid over interlacing branches. Responsibilities in the village are clearly defined, Andrew said: “Men do the cattle grazing, settle disputes between villages, provide security during the night, and mend the fence around the village. The women work a lot: They build houses, do cooking, fetch water, milk cows, fetch herbs, and take care of the village during the day.”

Suddenly a line of women, resplendent in brilliant red, white, yellow, and purple robes, long dangling beaded necklaces and large looping beaded neckbands, assembled in the middle of the village and began to chant. “They’re welcoming you,” Andrew said, as they smiled and their voices rose into high-pitched cries.

After our welcome, Andrew invited us into a typical hut. It was dark and stuffy—small triangular windows latticed with branches were the only source of light and ventilation—but as my eyes accustomed to the light, I could make out a room lined with cattle skins. “This is where the adults sleep,” Andrew said. He motioned toward the skins. “You can touch them.” I reached out and ran my fingers over the soft-prickly hair that covered the skin, and tried to imagine what it would feel like to sleep on that thin spread every night.

“Here is where we cook,” Andrew said, walking into the next room and pointing at a fire pit in the middle. Flies buzzed drowsily, and the scent of smoke hung in the air. “This is the children’s bedroom,” he continued, moving into the next room, which was lined with more skins for sleeping. Then he pointed into a dusky corner, “And that’s a room for the goats over there.”

Though the air was hot and close and seemed to cling to my skin, something kept me in that hut. I tried to imagine waking up to the first gray light of dawn seeping through the latticed windows; walking out in the morning air to tend the cattle; cooking around the fire pit, the smoke penetrating every pore as it curled lazily toward a tiny opening in the ceiling; eating around the fire; falling asleep on the cattle skins to the breathing of the goats and the sounds of the encroaching night. “Next time you visit, you can sleep here as my guest,” Andrew said, and his eyes flickered with a warm light.

On both of my safaris, close encounters with the landscape, the wildlife, and the people have conferred one more kind of life-expanding magic: a connection to the wildness in ourselves. I first experienced this poignantly, and life-changingly, on the last night of my safari in 1976.

After our dinner around the campfire, the others retired, and I was left alone outside my tent. The silence was unreal, all-encompassing, and united with the dark in some primeval symbiosis beyond my understanding. The African night seemed thick with history and time and legends whose language I could not decipher.

I looked around and tried to comprehend the plains and the trees and the stars that would outlast me. I thought about the animals and the villagers beyond, and about a continuity that stretched incomprehensibly deep into the past and unimaginably far into the future. I was a tiny pinprick in the vault of space and time. And yet, something stirred inside me, a wild place that reverberated, resonated, with the wildness outside. In that moment, I understood: There was an Africa within me too.

For a while I lost myself to sky and grass, tree and star, to this singular place and moment, sufficient in and to itself.

Then I awoke as if from a dream, and took out my journal and wrote: “The African plain is wild and peaceful, brooding and benign. It is in this sense an extension of self, a macrocosm that magnifies my own dreams and doubts. As I approach the end of this journey, I feel that Africa has assimilated me into deep and secret rituals of being that transcend customs and societies, somehow unknown and yet familiar, unfamiliar and yet known. In Africa the self is lost in the trees and plains and mountains and endless sky, and yet on leaving it is returned with a new capacity for knowledge and a new affinity for appreciation, of man and of the creations and processes beyond him.”

That’s how I felt in 1976, and I feel exactly the same way today. There is a magic waiting in the bush, a wild connection that will forever change your sense of the world – outside and inside. Once you venture deep into the heart of Africa on safari, you never leave. It pulses inside you, and around you, wherever you may be.

************************************

Ready to experience the magic of visiting Africa? Fill out our interest form or call our team at 888-570-7108, and you’ll be making your own safari memories.

Dear Don, I so enjoy reading your travel blogs. As I read your words, I can feel your sense of joy and wonder. I admire your ability to think deeply about your experiences and share them with the world, helping us to do a little soul searching about our own adventures and keeping us curious! Safe travels my friend! I look forward to more adventures. Leane

Thank you Don for another heartfelt blog allowing us to understand the thrill and joy of traveling around the world. Yet there is something an extraordinary about the safari experience. It grounds you, it evokes the nature “beast” inside us, it gives us meaning to what is like to live with and around nature, and it gives us an appreciation that Africa tries to hold onto it’s/our history and traditions that often gets over run by modernity. We have been on 6 safaris (two in the Serengeti, one in South Africa, one in Namibia, two in Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe). The… Read more »

Thanks for giving us a “taste” of Africa!! Amazing!!!

Absolutely beautiful, just what I always expect to find in your writing. I felt the magic and wonder of your journeys. Always life-changing and profound. You show us how travel changes so many ways of thinking. Thank you for sharing your wondrous adventures with us.

You have led an exceptionally charmed life that you share with us so evocatively. Thank you.

What a beautiful description of your safari experience. I have been on three safaris – two in Tanzania’s and Kruger last November and I’m planning another trip to Kruger next May.

You’re spot on – there is a magic to being in Africa and it does call you back. I say it’s my happy place and it is. It’s life-changing, in my opinion.

thank you again for your very beautiful eloquent description…

Hi Don George, I, too, visited Kenya and Tanzania in 1976. At the time I was a young doctor in NYC during my first year of full time work following fellowship. A friend of mine and her recently wed husband, both also doctors, had decided to live in Nairobi to practice medicine for a few years before settling back in the U.S. They invited me to visit them in Nairobi, which included about two weeks on safari in their jeep. They provided all the camping gear and necessary food – our first stop was Arusha, then Masai Mara, Serengeti, Ngorogoro… Read more »

Dear Andrea, What a wonderful and evocative note. Thank you so much! Your memories are thrilling to read — sleeping in small tents with the growling of lions and hyenas all around you. Goosebumps! And thank you for traveling with GeoEx to South Africa and Botswana. I am so happy that you found the same magic still there 40 years later. As we both know, it awaits you on your next trip too! Wishing you many more joyful adventures to come! — Don