The Coffee Ceremony

By Kaui Hart Hemming

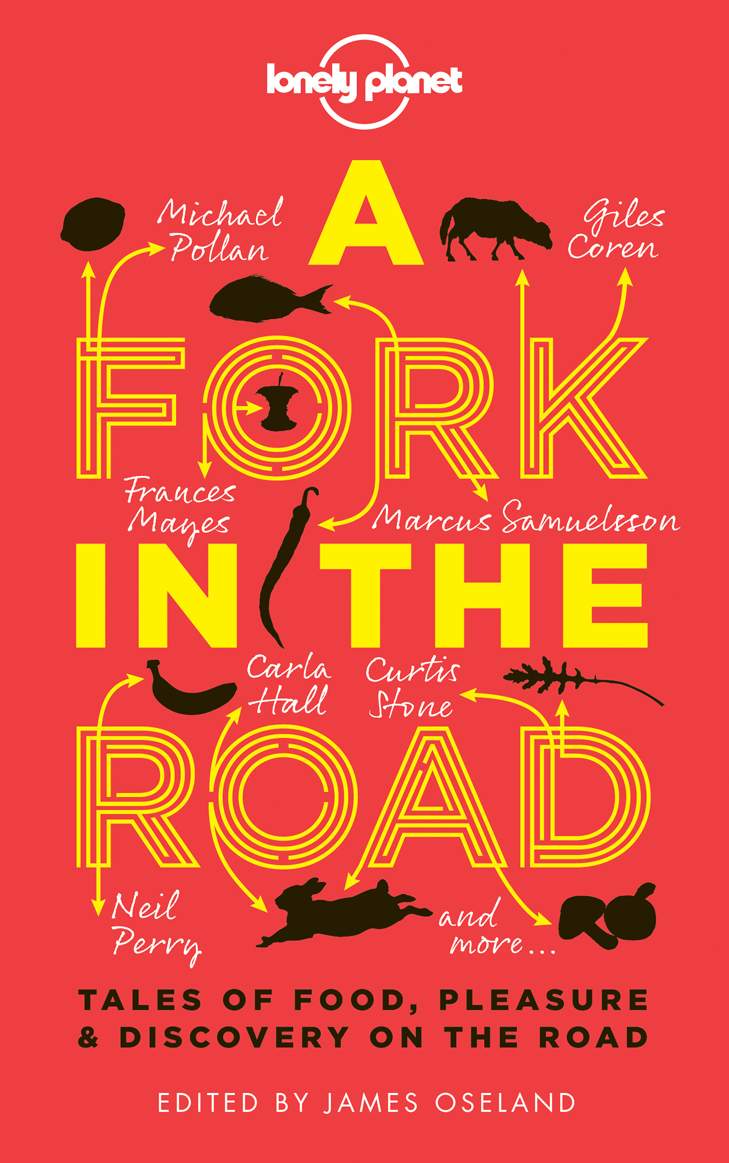

Editor’s note: Lonely Planet’s new anthology, “A Fork in the Road,” presents 34 stories that explore the intersection of travel, food, and cultural revelation. Each of the pieces in the book, writes editor James Oseland in his introduction, “says something ineffable about how we process and remember tastes and sensations, and about how they alter our view of the world.” The poignant story we excerpt here, by Kaui Hart Hemming, exemplifies the riches of this collection. Hemming’s first novel, “The Descendants,” was published in 22 countries and made into an Oscar-winning film. Her next novel, “The Possibilities,” will be published in 2014. Follow her travels at http://instagram.com/kauihart/ and https://www.facebook.com/KauiHartHemmings.

I drank coffee every morning, usually at the kitchen table while checking my email. I’d drink it while walking around the house, herding the family toward their various checkpoints—breakfast, teeth, backpack, lunch—before work and school in Honolulu, Hawaii. Then I’d sit down again with my coffee. Laptop open. Morning news on. I almost always drank alone.

My solo java routine was interrupted when we went to Addis Ababa to finalize the adoption of our son. We had already travelled there less than a month ago, but this time we’d be able to bring him home.

There’s a lot to do in Addis, a city perched on a plateau, bustling with students, markets, buses and goats. We visited Haile Selassie’s former palace, the museum that housed the infamous Lucy. We trekked down Bole Road, explored the nightlife, but it’s hard to be a tourist when you’re staying in a guesthouse with adoptive parents and children, some of whom have no one coming for them. Our sightseeing had more to do with wanting to know a place, store it somehow for future hunger.

There was a lot of down time, time in which we couldn’t go too far, time filled with coffee.

It’s ritual here, a way to gather, and it’s frequently drawn out for long periods of time. In coffee shops it seems people would sit and drink and talk for hours, never hunched over a laptop, rarely alone.

Coffee is woven into the society, into the history of Ethiopia, its origin. I learn that the growing and picking process of the beans involves over 12 million Ethiopians and produces over two-thirds of the country’s earnings, and I have to say that when I get back to the US I am bereft. I’m not a coffee snob, but the richness of it, the depth, is unfindable, or I just haven’t taken the time.

Time. That’s what this is really about. Taking the time to realize what you’re doing, what you’re drinking.

“It’s like their happy hour,” I said to my husband, who rarely drinks coffee at home, but did so regularly here.

“At all hours,” he said.

We watched people laugh and talk, similar to the way you do with friends in bars, discussing your day, your problems, the large and mundane stuff of life, chatter fueled by the buzz.

Every day, at least twice a day, we went to the Daily Cup, walking through the dusty streets. We’d go with another couple who had adopted a child from Rwanda, and we’d sit and talk and drink, trying to know a place, through its food and rituals and local clientele. We were cafe flies. We were outsiders, bewildered, far from home, trying our best to mingle.

On our last day before the thirty-two-hour flight home, we were introduced to the coffee ceremony, when I realized that coffee could get even slower.

It’s a common practice, not necessarily done on special occasions, but at our guesthouse, the staff were doing the ceremony as a way to say goodbye.

My seven-year-old daughter and I sat in the living room, watching the women who work at the guesthouse roasting the beans over a small charcoal stove. The smoke mixed with the burning incense, making it seem like something sumptuous and earthy was on fire. The two women were attentive to it, jostling and stirring, whisking away.

“We get the oil out,” she said. “And then we—” She made a motion with her wrist that I took for grinding by hand, then stirred and shook the husks away. When the coffee beans turned black she ground them by pestle and a long-handled mortar.

My daughter was bored—she was here for the popcorn that is always served with the coffee. I told her boredom was good for her. We watched the grinding and then the stirring into the clay coffee pot.

“Jebena,” the younger woman said, tapping the pot, which was round at the bottom with a straw lid.

Other guests came into the living room area. Music was playing and we talked about the days we had, and what was in store for us when we got home. Our son, up from his nap, was brought in by the nurse. He was so at ease in my arms. I smelled the top of his head, locking eyes with my husband, and I think you’d assume this was a tender moment, but our look also communicated bewilderment and awe. This was our ten-month-old son who we were about to bring home, whose last eight months of life had been in one tiny room, and sometimes a small outdoor courtyard where he was entranced by a single tree growing on the other side of the barbed wall.

We were completely out of our world, about to take him out of his, and during my time here I kept wondering how to bring a part of this city home—for us, for our son, for our family. The coffee ceremony was satisfying some of this yearning. The women were singing, the smoke was in the air, and then the coffee was being served expertly—the pot held high above the cup, and I felt like I was part of an archaic ceremony, an induction of sorts, and the ritual seemed to be just what I needed to mark this time, to reduce many emotions into a taste, into an unforgettable blend.

I took a sip of the coffee—it was beautiful, though probably more so because of the process itself, the gift of it and the time it took, the elegant steps. It was a kind of culinary tai chi, though not quiet or solemn—I wouldn’t have liked it as much. The women spoke loudly—and they were usually quiet in the kitchen and soft -spoken with us. People were laughing, kids playing on the floor.

The coffee was making another round and the translator told us that after this, one more cup would be served, the grounds are brewed three times.

“Awel is first cup,” he said. “Then kale’i. The third is bereka.” I didn’t think I could take another. Just one cup felt like three shots of espresso.

“It is rude to stop halfway,” the translator said, as if reading my (and perhaps everyone’s) mind. “The third serving is a blessing.”

Well, then. I kept drinking, wanting to be both polite and blessed, and wishing the same could be said for a third glass of wine. Voices were getting louder, laughter seemed more deep and true. We sat for more than an hour, and it made me think of all the times I carefully prepare dinner only to have it virtually chugged, the set table abandoned within twenty minutes. I wanted to take this ritual home with us. I wanted to take back the slowness.

I was on the last cup. There was a lift in my voice, my face and heart. I got the sensation of being so far from home, and yet finally embraced—which always seems to happen when you’re about to leave a place. We were embarking on something, changing the voltage of our lives.

Food and drink is so much more than food and drink. When we consume them we are engaging in a backstory—the effort and attention, the craft and history, the community and connection, and the ritual itself, which harks back to unknown people and places. A coffee ceremony—I see us from a distance, a nook on the planet, and like the aroma and smoke: rising, blending, disappearing all together.

Our son is three now. I drink my coffee with him in the morning. I still bustle around, making lunches, checking email, and he sits at his little table eating his cereal and he tells me in his somewhat Italian-sounding voice: “Sit, Mommy sit. Right here. Sit,” and I sit and I slow down, and I drink the things behind the coffee, remembering that moment. Food, a feast, a single bite, a sip—they can uncork those memories wherever you are. You can take it with you.

This story is adapted from “A Fork in the Road,” (c) Lonely Planet 2013, reproduced with the permission of the publisher.