Reimagining Greenland Inuit Culture: Resilience in Wood

Being a “Northern person” has nothing to do with where you live. Northern people like winter, snow caves, icicles, and glaciers. They like sled dogs and sparsely populated areas.

I most definitely am a Northern person. Since I first read Benedict and Nancy Freedman’s now-classic 1947 book Mrs. Mike as a child—which takes place in the blizzard-and-grizzly-bear regions of Northwest Canada—my heart has been with the Arctic and the people who live there. That’s why when I’m able to travel, I try to choose cold climes.

But there’s another reason I shoot for the Arctic, every time. I think winter is an endangered species. And I want to see it in all its permutations before it’s gone forever. Too, I want to meet the people who thrive in the planet’s cold places. They seem to possess the secret to resilience: answers to life that are sorely needed today, everywhere, and that could also melt away in a warming climate.

In a way, then, I’m an extinction tourist.

But I’m not the only one. Warming temperatures in the Arctic have opened it up to tourism like never before. As little as 50 years ago, before rapid climate change was being felt all over the Earth, most of the people who traveled to the Far North were climatologists, glaciologists, seismologists, explorers, or ethnographers. But now, warmer weather is luring large numbers of leisure travelers to small, Inuit communities. Some fear that local traditions and cultures will soon die out, and that local infrastructure and other resources could be stretched too thin by a sudden influx of more individuals.

Will the Inuit and their unique Northern cultures and traditions be able to survive such changes? Will the resilience they needed to develop in order to live at the world’s cold top prove to be enough to withstand today’s double threats of climate change and tourist inundation? Is sustainable tourism in the Arctic truly possible? I went to Greenland twice to find out.

Climate Change Chains

It’s an age-old conundrum that thoughtful and compassionate travelers often grapple with: While we want to see the extraordinary, the rare, the seldom-witnessed, and the little-visited, does the fact that we do so change those things forever? Does engaging in our travel desires and quenching our thirst for adventure ultimately hurt the places we visit?

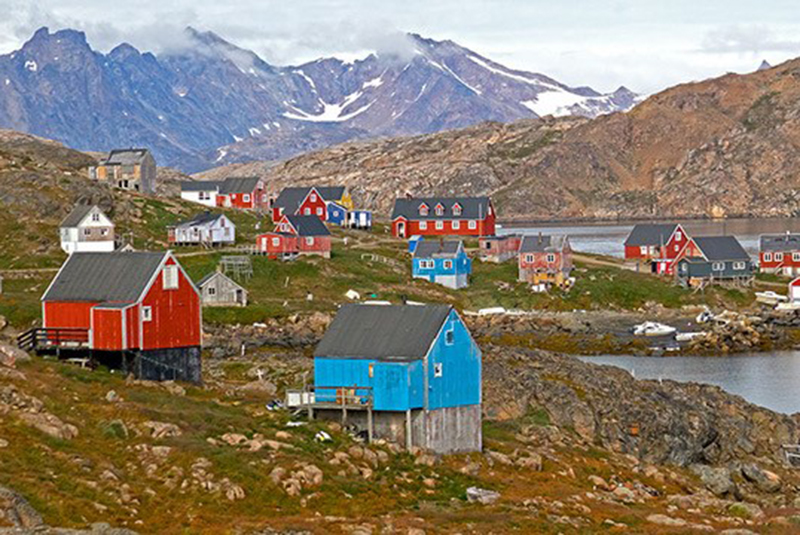

The first time I went to Greenland, in 2013, my tour was ship-based. It promised everything a Northern person like me wants in a great travel journey: bleak beauty, glissading glaciers, impossibly high icebergs, and isolated Inuit villages. Our boat navigated around the lower half of the Earth’s largest island, from the more populated (if “more populated” even applies in Greenland) west coast, where the capital of Nuuk is located, around the southern edges to the wilder east coast. Along the way, we made stops at villages—where the small homes were painted in bright hues of blue, red, and yellow—for soccer games and coffee klatches, called kaffemik in Greenland.

It was in the settlement of Tinit that I learned firsthand how climate change is now affecting Greenlandic communities. Our tour group was invited for kaffemik in the home of the grocery store’s manager, who is also an Inuit and a subsistence hunter. Our interpreter asked if he had experienced any effects of warming temperatures. He said he had. “The seals used to be plentiful and fat,” he explained, “but now, there aren’t as many—most go farther north. The ones that are here are thinner with not as much meat, and their fur isn’t as nice.” He said there was no doubt in his mind that things are changing quickly in Greenland.

Scientists would agree with him. The food chain here is at risk. Algae that grows on the underside of sea ice is eaten by zooplankton, which is then eaten by fish, which in turn are eaten by seals, that finally end up in polar bears and humans. However, if the first link, the algae, disappear because sea ice is melting, the whole food chain breaks apart.

There are more problems rising to the surface as the sea ice disappears. The frozen highways on which the Inuit ride their dogsleds and snowmobiles are vanishing. Communities are becoming increasingly fragmented. And, as the great Greenland ice sheet rapidly melts, the island is opening up to mining, oil drilling, and increased shipping, adding even more environmental woes. Mass tourism is only going to make this worse.

I wondered how Greenlanders would handle the challenges of piloting their way into the future. And then I went to Greenland for the second time, in the summer of 2017.

Economic Nomenclature

This time, my base of operations is on land. The tour I joined spends several days camping on the east coast of Greenland near Sermilik Fjord, located about 66 miles south of the Arctic Circle. The nearby settlement of Tasiilaq has about 2,000 residents. Some of the former ones rest in a cemetery just outside the village.

The rows of white crosses that stand starkly and somewhat sheltered in a shallow, wide valley in front of the blue-gray mountains are poignant for the hardscrabble lives they represent. They seem to mirror on land the white bergy bits that mark the waters of the fjord, a sea of white back here, juxtaposed on the icy one out there.

But even more striking is the fact that neither the crosses nor the graves themselves bear names. When I ask my Inuit guide why, he tells me that many of the names of the deceased will be given to children in subsequent generations. The dead have no need of monikers now, whereas those being born do. In other words, the names are recycled.

It’s a matter of economy.

I later see this same parsimony in the face of an Inuit storyteller who performs for us one afternoon in Kulusuk, a settlement in southeastern Greenland with a population of about 270. As we sit on the rocks above Torsuut Tunoq sound and watch the sun slip lower in the sky, an elderly man steps before us, begins to beat his polar-bear-skin drum, and starts singing. Our interpreter explains that this first tale is about Raven creating the world.

Somehow, in the spaces between the rhythmic drumbeats and the Kalaallisut words, this keeper of his culture’s history manages to contort his facial muscles into a wide range of expressions as he gets deeper and deeper into his performance. By his visage alone, he transforms himself into as many as five or six distinct characters. And even though I do not speak Greenlandic, I know exactly which one is speaking, just by a change of his countenance.

At times, his face looks precisely like an iconic Inuit mask, the kind you often see in museums or gift shops.

Trees Turned Tupilaq

Selling items to tourists in museums, gift shops, and workshops has helped the economy of many Greenland villages. And one of the most popular souvenirs is a tupilaq.

Traditionally crafted in feathers, hair, leaves, or skin, tupilaqs protected their owners against enemy attacks. The small figurines were created in secret, private places; then, after some chanting, they were cast into the sea to seek out an enemy with the intent to kill. However, if an enemy was more powerful (in a magical way) than the aggressor, then he or she could turn the tupilaq’s powers back against the maker.

Because they were created largely with natural, perishable materials, no original tupilaqs remain. And since they were usually thrown into the sea, they were also not intended to be seen by any other person.

When Europeans first began traveling to Greenland, however, they became curious about tupilaqs and what they looked like. Some Inuit then began carving figures in whale bone, reindeer antler, or narwhal tusk for tourists to buy and keep. The craftsmen quickly learned that the more fanciful and grotesque the design, the better the items would sell. Tupilaq carving morphed into a highly skilled art.

During my two tours in Greenland, I had picked up several tupilaqs made of antler bone. But the last one I purchase at a small shop in Kulusuk seems stranger than all the others and out of place because it’s made of wood. The handful of trees and bushes (common juniper, downy birch, grayleaf willow, Greenland mountain ash, and mountain alder) that are indigenous to Greenland currently grow only in very small plots in the south. This tupilaq appears to be made of oak.

I ask the seller where the artist could have possibly gotten the wood. “He probably just used an old piece of furniture,” he replies.

It’s in that moment that I know that the Inuit culture will never be lost. It’s far too malleable, way too flexible, and eminently too resilient to disappear. It will remake, refashion, and remodel itself, no matter what the world throws at it.

The evidence is all around me: Recycling the names in a cemetery, reconfiguring the face of an Inuit storyteller, and reshaping an old piece of furniture into a new life, sold to another Northern person, like me.

Contemplating this, I reappraise my own role, too: I have not come to Greenland as an extinction tourist, but rather as a Northern person who revels in reimagination.

# # # # #

To find out about the many ways to explore Greenland, or any other of our far-flung destinations, give GeoEx travel specialists a call at 888-570-7108.