On Getting Lost

Getting lost comes with the territory of adventure travel. But you don’t have to travel halfway around the world to know the terror—and eventual treasure—of losing your way. As this evocative essay by Bay Area writer Kim Fortson shows, it’s quite possible to get thoroughly lost in your own back yard.

“Stop!” Richie yelled.

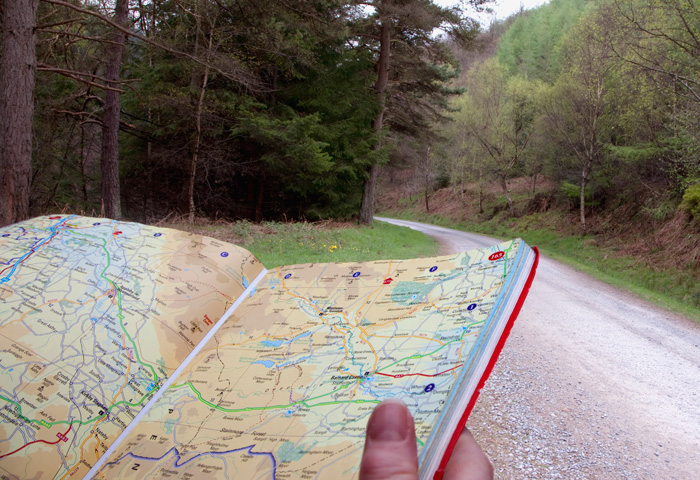

Eight sweaty bodies slinkied to a halt. It was approaching dusk in a state park in Napa, eight miles into what was supposed to be an eight-mile hike, and we were lost. My boyfriend, Richie, hovered over a map with my friend Brian. We waited.

The trail we’d been following up, down, and sideways (but mostly up) through a terrain of mud, stone, and head-high overgrowth had simply ended. In front of us, granite-colored rock faces zigzagged with greenery. To our left, 10 feet beneath us, a frothy creek squeezed between calloused sheets of rock.

Richie and Brian motioned for us. We missed the trail here, Richie explained, tracing the map with his finger. To catch it, we’d have to backtrack for about three-quarters of a mile. Then we’d have to walk another few miles before we met the road. Or, he said, we could follow the creek and cut a path that led, if we aimed correctly, straight to the parking lot. But there was no guarantee of getting through.

Tired, sore, and, at this point, very smelly, we conferred. The sun inched closer to the tree line. There was another hour, tops, before the daylight completely waned. We were supposed to be back in the city by 8 p.m. Our casual hike was quickly transforming into a conundrum with every subtle dip of the sun’s yolky rays.

There is, in both popular and travel literature, a romanticized view of getting lost. Books are devoted to it, columns champion it, guidebooks paradoxically tell us how to do it. Get lost, we hear, in speeches and television shows and Pinterest boards pasted with picturesque platitudes, and we’ll be found.

But when confronted with the reality of lostness, the scramble-down-this-slope, hop-across-these-stones-and-try-not-to-fall-in-the-water kind, the notion loses some of its poetry. This is mostly because when you are actually lost, you are not really sure if you’ll be found. Or when you’ll find yourself. Or if you’ll remember what you’re supposed to be learning in the midst of all the losing and finding that you’re doing.

In one sense, we were the lucky kind of lost. When we pressed forward, we slid down the creek bed and teeter-tottered on slippery rocks that formed a path for us to cross. We rounded a corner to find a waterfall spilling from the creek. Beneath it, icy water, serpentine-hued, pooled, then jostled to rush through a gap between two steep cement blocks. Some members of the group embraced the moment and braved the cold with a spontaneous swim.

In a different sense, we faced another problem. The two cement blocks beneath the cascade were part of a dam, and the only way forward was to cross the gap and slither down a rink-a-dink ladder whose rust-tinged rungs looked like they hadn’t seen feet in years.

This is where getting lost gets you—once you’re in the midst of it, you have to follow through. You have to show up, hold your breath and actually live out the mantra that sounded wonderful when it was innocently posted on the bulletin board behind your desk.

My ever-adventuresome friend Rachel, whom I’d coincidentally met on an adventure trip abroad, fearlessly hopped over the crevasse and descended the ladder.

“It’s not that bad!” she called.

The typically cautious Holly fearlessly followed Rachel. I followed suit.

One by one, we thwarted the gap and pitched our legs over the ladder’s wobbly handles, contorting our bodies to fit between the narrow rungs and making our way to the soft soil floor. When we all reached the bottom, Juliana pointed out the view. Surrounded by towering rock walls draped with emerald mosses, yet another vibrant waterfall and the rusted frames of man-made metal work, we felt as if we’d stumbled upon ancient ruins, constructed with careful precision and slowly forgotten over time. It took me a moment to remember we were only an hour north of home.

We footed the rest of the journey with relative ease, passing overgrown campsites and disintegrating port-a-potties, clusters of picnic tables turned every which way. On one, a single bottle of beer stood stubbornly upright, as if in sign of solidarity.

A final obstacle blocked the end of our trail—a razorwire fence. Behind it, from the direction in which we’d just come, a sign warned against visitors. “No Trespassing,” it said. “Mountain lions, poison oak…”

We exchanged glances and nervous laughs, relieved that, with the sun now fully out of sight, we hadn’t come across either. A shoddy hole in the razorwire was our only option for exit, and we ducked through it, at last on a path we recognized.

When we found the parking lot, our cars mercifully still parked where we had left them, Rachel led us in a round of stretches. As I coaxed my hamstrings, circled by friends and the rosy dusk settling around us, it occurred to me that what truly makes getting lost so magical isn’t necessarily grand revelations or sweeping personal insights (though not to say they don’t sometimes arrive). It’s the small moments, the little leaps of faith, the renewed appreciation for an old place, the ability to laugh at your foolishness and your stubbornly tight hips, the decision to press forward when you could have gone back.

At last loose and somewhat recovered, we piled into our respective cars and turned back toward the city. For a moment none of us said anything. Then Richie hit the gas. We were going to be late.

# # # # #

Find your next adventure with GeoEx, choosing from more than 100 destinations.