Hemingway, Cuba & Me

Editor’s note: This extraordinarily poignant story by author Anne Sigmon won the 2018 Book Passage Travel Writing Award, chosen each year at the conclusion of the prestigious Book Passage Travel Writers & Photographers Conference. We are deeply pleased and honored to publish it here. The story subsequently received an honorable mention in the Society of American Travel Writers’ Lowell Thomas Awards.

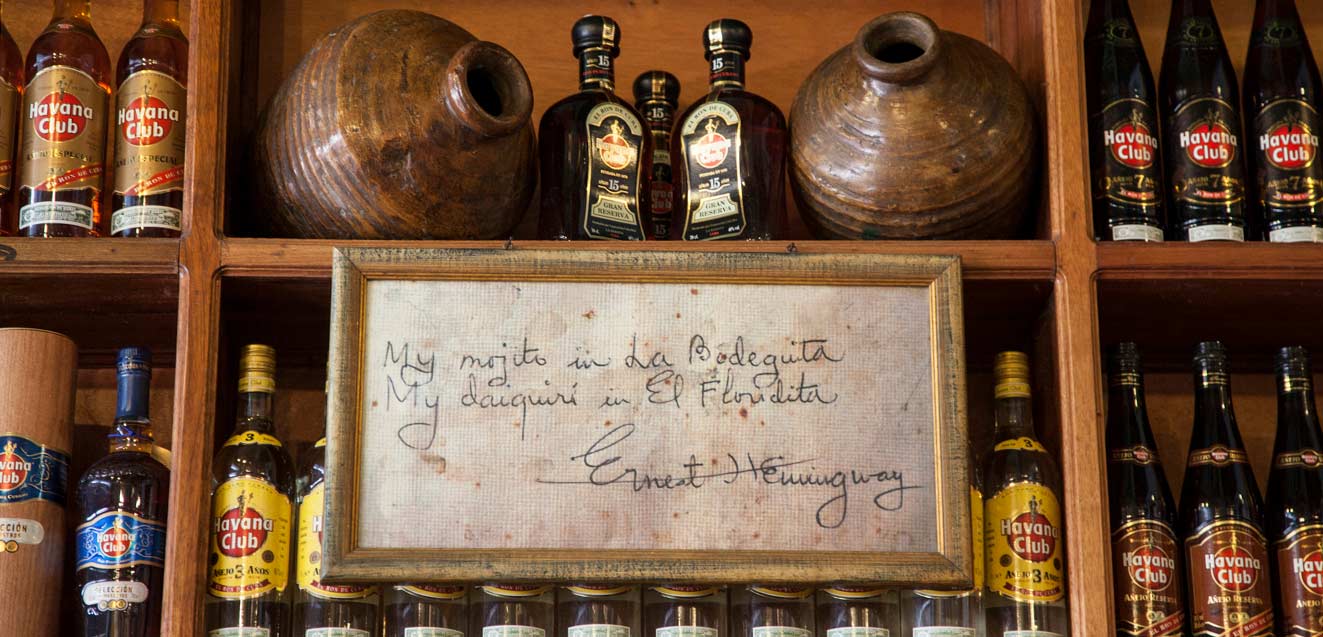

The two Papa doblés knocked me on my ass. Those sour grapefruit daiquiris had a kick. After all, they were his favorite. The crowd was three deep at the bar, everyone grooving to an all-girl salsa band at El Floridita, the Havana nightspot famous as Hemingway’s preferred watering hole. Barkeeps in red waistcoats churned out daiquiris a dozen at a time, sliding them down the timeworn mahogany surface.

I had no business being there: me, a brain-damaged stroke survivor maxed out on blood thinners. Drinking of any kind was dicey—much less carousing in a bar. I was pushing it, but I didn’t care. I had come to Cuba to feed my decades-old fascination with Ernest Hemingway as both writer and fearless adventurer, and to explore why I still loved him when much of the critical world had turned to harsh reappraisal.

I fell in love with Hemingway in freshman lit. After a semester of Henry James’s mind-numbing parlor games, I pulled an all-nighter reading A Farewell to Arms—not because I’d fallen behind, but because I’d fallen in love. I was captured by Hemingway’s raw adventure: the hot breath of the leopard, the marlin exploding from the Gulf Stream, breaking to run free.

Years after college, I courted adventure with my audacious husband, Jack. On Mount Kilimanjaro, we snuggled in our sleeping bags reading The Snows by flashlight. On safari in Kenya, we devoured The Green Hills of Africa in the afternoon heat. We hit Pamplona for the Feria and perched at Café Iruña reading The Sun Also Rises.

Our travel is tamer now and I am more fragile. In addition to stroke deficits and blood thinners, I’m embroiled in a lifelong battle with a nasty autoimmune disease. I’ve made concessions, but nothing could force me to miss a rendezvous with friends in Cuba last year. Though disappointed that Jack couldn’t join me, I was determined to have the “full Hemingway” experience.

* * *

La Floridita, Cuba

As I nursed my second Papa doblé at El Floridita, I studied the life-sized statue standing in the far left corner—Hemingway’s spot. Frozen in bronze, the rugged writer stood, elbow on bar, radiating a mischievous charisma. I swear there was even a twinkle in his eye. Though it charmed me, the scene felt wrong. As I finished my drink, it hit me: The bronze Hemingway at El Floridita sports that iconic close-cropped beard so much associated with his image. But—remembering his biography—I realized that, by the time he grew the beard, he’d lost the twinkle. By then, he was deep into his querulous “Papa” period. In public, he was often drunk or rude or both.

Hemingway wasn’t like that when he first came to Cuba. “The man I remembered was kind, gentle, elemental in his vastness,” his son Gregory once wrote.

The author found respite from fame in his fifteen-acre farm—La Finca Vigía—in the village of San Francisco de Paula, about 10 miles southeast of Havana. He made friends with the local fisherman and recruited village boys to play baseball with his three sons.

The day after I visited El Floridita, I set off down the Carretera Central to see Hemingway’s home for myself. The one-story Spanish colonial is the color of pale sunshine, hidden in a serene woodland of royal palms and bamboo. Tall windows and French doors open to the breeze that Hemingway loved. Inside, the house is a temple to his vast intellect and interests. In room after room bookcases sag with the weight of thousands of his books. The walls are crowded with hunting trophies and expressionist art.

Hemingway had several desks at the finca, but his favored spot was a simple bedroom where he wrote standing up using the top of a bookcase for a desk. I paused there to breathe in the magic at the shrine of his rusting Royal typewriter.

* * *

Papa Hemingway

Some say Hemingway did his best writing in Cuba. In his early days on the island, he wrote much of For Whom the Bell Tolls, my personal favorite. But after its publication in 1940, he faced a tortuous 12-year creative drought aggravated by a series of injuries.

Many scholars cite Hemingway’s notorious drinking, plus a family tendency to bipolar depression, for his late-career slump. Malicious whispers charge that he allowed his fame to eat him alive.

But a new book, Hemingway’s Brain, by forensic psychiatrist Dr. Andrew Farah, says otherwise. Although there is no question that Hemingway was an alcoholic, Farah concludes that his primary illness was dementia brought on by repeated head injuries. Farah identifies the disease as CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy), the same brain affliction currently getting worldwide attention for its crippling effects on football players. It’s progressive, devastating, and, even today, there is no treatment and no cure.

Ever the macho adventurer, Hemingway suffered at least nine serious concussion injuries in 25 years, Dr. Farah found. They ranged from the World War I explosion that almost killed him at age 18, to car wrecks, boat accidents, and two plane crashes in 1954.

As Hemingway’s brain deteriorated over the last years of his life, he found it harder and harder to write.

I imagined him standing in his bedroom at the finca. Wearing old moccasins and a ratty shirt, he stood on a tattered animal-skin rug at this writing station. Staring at the empty page, he jabbed the nub of a pencil in fury. Did he notice the meadowlark singing in the garden? Or was he consumed by the silence in his head?

While I was there, I re-read his book Islands in the Stream, one of only two he set in Cuba. I was struck, not by the prose, but by the heartbreaking flashes of self-awareness as writer and protagonist seemed to merge. The Hemingwayesque character describes aggression welling up like a tide. “He could feel it all coming up…. He did not know what made him feel the way he did….” He chides himself: “You faker. You cheap phony. You rotten writer….” The more Hemingway struggled to write, the more surly he became.

Then, suddenly, the fog cleared. In one final, epic clash, Hemingway fought the ocean of his unruly prose until it gave up Santiago, his Old Man and the Sea. In this book there is no drunkenness, no railing at fate—just one exhausted old man battling for his life with supreme determination. In a six-week creative explosion, Hemingway honed a story that had been percolating in his mind for decades into one of the finest performances in modern literature. The book, published in 1952, resurrected Hemingway’s career and propelled him to the Nobel Prize in 1954.

His moment didn’t last. Not long ago, I watched a television interview taped just two years after he finished his masterwork. Hemingway’s struggle with language is agonizing. In the video, he looks down, speaks slowly, almost woodenly, at one point dictating punctuation as though he’s writing. I winced, seeing him fight to fish words up from the depths. It was a brain-damaged effort I recognized all too clearly.

* * *

Ernest Hemingway and Cuba

When I returned home from Cuba, melancholy fell over me like a blanket. I was tired and sad to be reminded of the misery that had shadowed the last 10 years of the author’s life. Plus, I had my own secret torment. Like Hemingway, I could barely write. Over the past two years, my cognition—damaged by that stroke 15 years ago—has been steadily declining. Words are harder to find; my typing grows more atrocious every day. I am too easily overwhelmed. Papers pile up in my office. Whittling a story from a box full of notebooks is a monstrous task. I feel like I am slipping toward the edge of my mind. Despite many consultations with doctors, no one can tell me how to stop the slide. Instead of lashing out like Hemingway, I drift. I ignore the phone, cancel dates, and burrow into myself.

After weeks of ennui, suddenly I understood what had happened to Hemingway with Islands in the Stream and his other unfinished books. He could no longer manage his material. He couldn’t separate the tip of his story from the gargantuan iceberg below.

That’s when I felt a different kind of kinship with the writer I’d adored in my youth. I don’t share his colossal talent, his outsized personality, or his vicious demons. Still, I know the terror of sensing my mind fading away.

In his last years, Hemingway roared like a wounded bear. I forgave him for that, and the forgiveness deepened my appreciation of his work. He’d known all along what was happening to him, just as I know what’s happening to me.

I went to Cuba to discover Hemingway. I never expected a lesson in how to face my own life-altering illness. In tormented dementia, Hemingway did not go gentle into the night. As for me, I hope I’ll handle it differently. I’m praying for the qualities shared by his best characters: courage and grace under pressure.

# # # # #

If you’re interested in your own visit to Cuba, give us a call at 888-570-7108 to discuss the options for group trips, custom journeys, and family adventures.