Chasing the Tail of Chiuchow

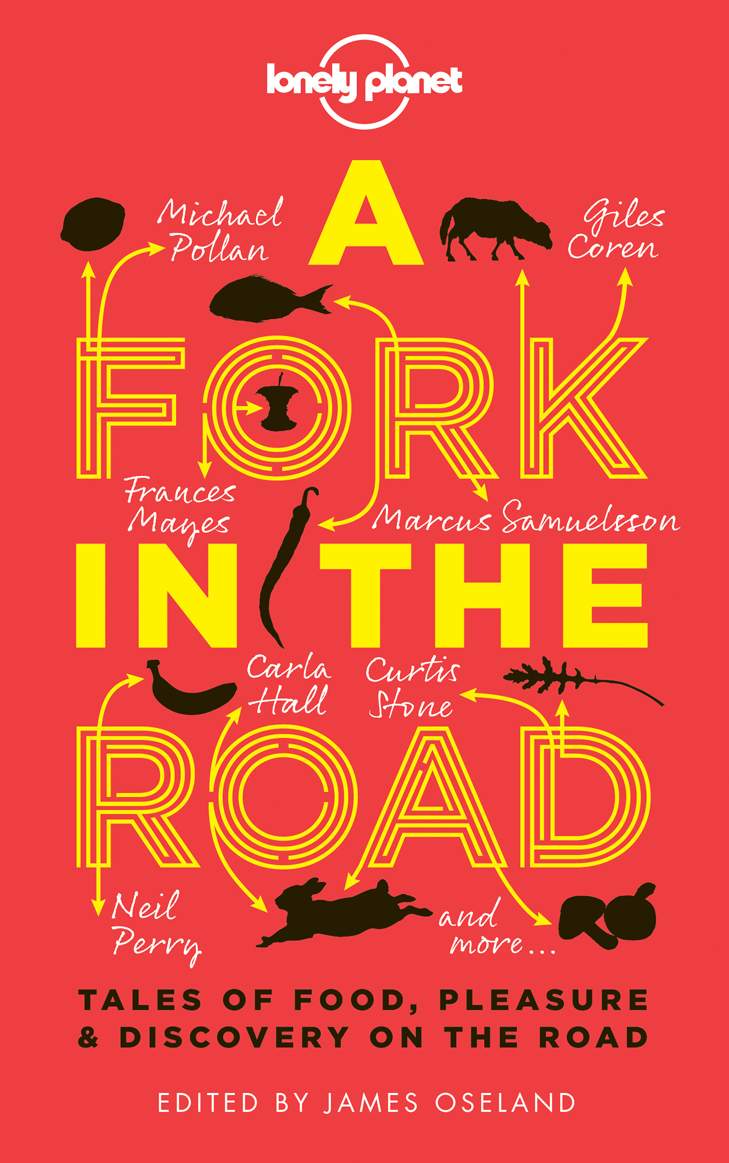

Editor’s note: Lonely Planet’s new anthology, “A Fork in the Road,” presents 34 stories that explore the intersection of travel, food, and cultural revelation. Each of the pieces in the book, writes editor James Oseland in his introduction, “says something ineffable about how we process and remember tastes and sensations, and about how they alter our view of the world.” Below we excerpt a deliciously illuminating story about a little-known Chinese cuisine by Fuchsia Dunlop, a British cook and writer who specializes in the foods of China. Dunlop has written four books, including the award-winning “Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper: A Sweet-Sour Memoir of Eating in China.” Her work has appeared in numerous publications and she won James Beard awards in 2012 and 2013.

By Fuchsia Dunlop

It was noon in Shantou, the southern Chinese river port also known as Swatow. A party of chefs and food writers had gathered around the table, and lunch was about to begin. The waitresses started bringing platters of food from the kitchens: stewed goose with all its accoutrements, cold fish with yellow bean sauce, and tiny fried shrimp. As each beautiful dish emerged, it was greeted with a round of lusty noises of appreciation: Pwooargh! Ooooagh! Phfooagh! After nearly two decades of eating my way around China, I’d never heard anything like the raucous joy with which these Chiuchow gourmets expressed their approval of our lunch.

Cantonese cuisine is supposedly the best known of all China’s regional cuisines. It was Cantonese immigrants who flocked to the American West in the nineteenth-century gold rush, bringing with them their own ingredients and setting up the first Chinese restaurants in the country. Even today, most Chinese restaurants in the West offer dishes that are, broadly speaking, Cantonese, such as sweet and sour pork and lacquered roast duck. But perhaps because

Cantonese cuisine seems so familiar, its true sophistication and diversity are rarely appreciated. And for evidence of the complexity of Cantonese cuisine, one need look no further than the Chiuchow, or Chaozhou, cooking region in Guangdong province.

This tiny pocket of northeastern Guangdong, named in English after its ancient capital Chaozhou but these days dominated by the modern metropolis of Shantou, is home to one of China’s most thrilling little regional cuisines. There are hotbeds of Chiuchow cooking in Hong Kong and

Thailand, where immigrants from the region have settled, but if you live in Europe or America the chances are you’ve never heard of it. The only named Chiuchow delicacy that pops up with any regularity on mainstream Chinese menus in the West is the chao zhou fen guo, a translucent steamed dumpling stuffed with a mix of finely chopped pork, vegetables and peanuts. If you’re really lucky, you might come across some aromatic stewed duck made in the Chiuchow goose style, but in my experience, it’sa rarity.

I’d been chasing the tail of Chiuchow cooking ever since my first encounter with it in a small, cramped upstairs dining room in the Hong Kong district of Sheung Wan. There, thanks to my friend Rose, who brought me to the restaurant with some friends, I had my first taste of the region’s shellfish congees, raw marinated crabs, and strips of taro frosted with silvery sugar. From that moment on, I sought out Chiuchow food whenever I was in Hong Kong, mostly in the

Chiuchow enclave of Kowloon City, where shopkeepers chop their braised goose on wooden boards and the Chong Fat restaurant cooks up scrumptious regional delicacies. I longed to travel to the Chiuchow region itself, but it wasn’t until many years later that I finally made it there.

“Ma ma ma ma ma ma ma ma,” said Xu Jun, trying to teach me the eight different tones of Shantou dialect. They all sounded similar to me, even though I’m a Mandarin speaker.

But then the dialect of Shantou, the modern capital of the Chiuchow region, is notorious in China, where they say only native speakers can grasp its subtle modulations. (“The most difficult language in the world to learn,” one taxi driver assured me.) The proliferation of regional tongues is one of the great frustrations for a foreigner learning Chinese. You can slave away at your Mandarin, and develop a passing acquaintance with a few local dialects, but as soon as you visit a new part of the country, you won’t be able to understand a word people say when they talk amongst themselves. When it comes to food, however, this extraordinary regional diversity is a blessing, because the closer you look at so-called “Chinese cuisine”, the more it expands and proliferates, like a computer-generated fractal pattern.

Xu Jun, Zheng Yuhui and their friends took me in hand as soon as I arrived in Shantou, a grey metropolis in one of the industrial heartlands of southern China. Within a couple of hours, they had whisked me off to the home of a famous local food writer, Zhang Xinmin; to a market where we surveyed radiantly fresh fish and intriguing dim sum; and to the home of the secretary of the local gourmet association, who was putting the finishing touches to his precise mise-en-place for that evening’sgastronomic adventures. A large potful of pork, cuttlefish and Yunnan ham simmered away on a slow flame on his stove, perfuming the entire apartment. As we inhaled its gorgeous aromas, Zheng Yuhui showed me photographs of dishes he and Zhang had prepared for their dinner parties. From what I could make out, they spent most of their free time cooking in Zhang’ssmartly appointed kitchen, amazing their friends with magnificent dishes and then posting the pictures to their weibo accounts, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter, where they each have legions of followers.

In that huge private room at the Jianye restaurant, they gave me my first real initiation into Shantou cooking. I’d had the famous aromatic stewed goose in Hong Kong, but never with all its trimmings. Here, there was not only goose flesh, succulent and lightly spiced, with a garlic and vinegar dip; also, on separate plates were arranged creamy goose liver, crisp intestines, jellied blood, crunchy gizzards, wings, feet and heads, each laid on a bed of tender bean curd and drizzled with some of the bird’s delicious cooking juices. Later, we tried some of the seafood for which the region is also renowned, prepared with a minimalism I was told was typical of the local culinary style.

“We really emphasize harmony between nature and man,” said Zhang Xinmin. “We make stringent demands of our ingredients because, even by general Cantonese standards, our seasoning is so light. You see these crabs,” he said, gesturing at a pair of the opened crustaceans, resplendent with orange roe, spread out with their claws and legs on a platter. “They are steamed with no seasonings at all. In Sichuanese cuisine, you have many flavors used in combination; here, it’s all about yuan zhi yuan wei, the original taste of ingredients, with seasonings often added afterwards, as a separate dip.”

Sure enough, the crabs came with dipping dishes of garlicky vinegar, and the cold steamed fish with a punchy, fermented bean sauce from the town of Puning. Later, we shared an oyster omelet served with fish sauce speckled with pepper, and deep-fried shrimp balls with a tangerine syrup. “In the Qing Dynasty,” said Zhang, “this region produced most of China’s sugar, which is why you’ll find a certain sweetness in our food.”

While foreigners don’t even recognize Chiuchow as a separate cooking region, Shantou gourmets are fiercely insistent on the distinction between their own lively culinary culture and that of the ancient regional capital, Chaozhou. “Shantou people see Chaozhou as backward and bumpkinish,” Zheng Yuhui told me. “So if you ask a Shantou person if they’re from Chaozhou, they may be off ended. Moreover, you’ll always taste the finest food in Shantou.” Zheng vehemently rejects the term “Chiuchow cuisine,” preferring to speak instead of “Shantou” or “Chaoshan” (Chaozhou and Shantou) cuisine.

After lunch, I persuaded Zheng and his friends to take me on a tour of the old part of the city, a relic of its status as a treaty port imposed on China by the Western powers after the nineteenth-century Opium Wars. Nothing could have prepared me for this glimpse of the lost world of Shantou’s foreign concession, which was like a ghostly shadow of the old French quarter of Shanghai. One or two buildings, like the English post office, had been restored and were still in use; the rest, street after street, block after block of early twentieth-century tenements, had been left to crumble into the polluted air. Shrubs sprouted from roofs and ledges; weeds had insinuated themselves between bricks and mortar. A few residents had clung on, their brightly colored washing strung out on the shattered balconies, but most of the buildings were deserted. The whole quarter, I was told, was slated for demolition.

Before I left Shantou, Zheng took me for a breakfast crawl of the backstreets, seeking out some of his favorite snack shops. In London and Hong Kong I was used to the dim sum version of cheung fun, those slithery sheets of rice paste embracing plump prawns, deep-fried doughsticks or barbecued pork. Here, in a thriving breakfast café, cooks spread the thin layers of liquidized rice with broken eggs, minced pork, leafy greens, tiny oysters and prawns, steamed them swiftly and then roughly folded them. They served the pasta with a soy sauce dressing and steaming bowls of pork off al soup. In another café, we ate a soup of rice noodles and beef balls. The lean beef had been beaten by hand with metal cudgels, whipped up into a taut, springy state so the cooked meatballs were actually crunchy in the mouth.

Despite the withering scorn with which Shantou locals viewed the old city of Chaozhou, as a foreign visitor I found it irresistible. Although the city is now surrounded by ceramics factories, the historic part of town has the kind of sleepy charm that has been erased in many parts of China by reckless modernization. Under the colonnades of the restored Memorial Arch Street I found long-established snack shops and bakeries that pandered to the notoriously sweet tooth of the Chiuchownese. In the Hurongquan café I tried the house specialty, “Duck egg twists”, glutinous rice balls stuffed with bean paste and served in a sweetened broth with chunks of sweet potato, gingko nuts, silver ear fungus and the white grains known as Job’s tears.

Nearby, a bakery was turning out golden pastries impressed with patterns from their wooden molds, and stuffed with a scintillating sweet pork flavored with fermented tofu and garlic. Legend has it that this sweetmeat was born out of a labor dispute in the late Qing Dynasty. A disgruntled baker, so they say, stormed out of his job after an attempted act of sabotage, having mixed all the ingredients in the storeroom together: fatty pork, peanuts, sesame seeds, garlic, syrup, flour, fermented tofu and wine. The boss’s wife noticed that the mess had a captivating aroma, so she used it as a stuffing in the next day’s cakes, which were received by their customers with rapturous approval.

In one of the backstreets, I came across a few old ladies sorting tea-leaves with their hands on bamboo trays, and countless tea vendors. Chaozhou is the original home of gong fu cha, a tea-drinking practice that has become fashionable all over China. Roasted Iron Buddha teas are brewed in miniature pots, and the caramel-colored infusion poured into tiny bowls. The bittersweet liquid is as sharpening as an espresso coffee. In the Chiuchow region, it is served before and after meals, and at any time of day. In the slow streets of the old city, shopkeepers sit all day on wooden chairs outside their establishments, their tea gear arranged on china trays, sipping tea, smoking cigarettes and chatting.

Every morning, one lane in the southern part of the old town was thronged with market shoppers. Goose vendors stood before glass cabinets hung with their glossy birds, still warm from the pot, ready to chop them to order. A couple of sellers offered cooked, cooled fish arrayed in bamboo baskets. There were freshly made snacks: fluff y heart-shaped rice cakes stained green by mulberry leaves, rice-paste dim sum stuffed with fragrant chives, and little cups of steamed translucent dim sum stuffed with minced pork that had been fried with a salty pickle. A woman stuffed raw minced pork into pockets of tofu and sections of hollow bitter melons that customers could take home and cook for their dinner.

Even for a well-travelled Chinese foodhound like me, Chaozhou was full of surprises. Most amazing was the urban goatherd I met on a busy thoroughfare near my hotel. His four white goats stood, tethered, on a wooden cart on the back of his bicycle, looking curiously around at the traffi c and the neon signs, their udders bulging. He milked them as they stood there, bagging up the milk and selling it to passing customers. “Just boil it and it’s good to drink,” he told me.

By the end of my visit, I was beginning to have a richer sense of the Chiuchow style: of its cold, cooked fish with their pungent dips, fresh steamed seafood, rich congees, rice noodles, cakes and sweetmeats. From the outside, it might seem to be collapsed into a generic Cantonese style. From the inside, it was a vibrant culinary region with a proud sense of its own identity. Chaozhou, and Shantou too, were places to throw out all one’s preconceptions about Chinese food, and open one’s eyes to the seemingly infinite variety of the country’s regional cuisines.

This story is adapted from “A Fork in the Road,” (c) Lonely Planet 2013, reproduced with the permission of the publisher.