A Passage to Pakistan: My First Travel Adventure with GeoEx

While I have not been traveling far afield in person this year, the pandemic has given me time and motivation to travel another way: by excavating the archaeological layers in my garage. The whole known world is in my garage—or at least, the world I have known since I became a professional travel writer in 1980. Dustily arranged on wooden shelves are dozens of boxes filled with maps, brochures, notes, and photographs from my past journeys. On the floor around these are further dozens of sturdy sacks, backpacks, and duffle bags filled with more brochures, photos, and maps.

Sometimes I don my pith helmet and archaeologist’s gloves and wade into these ruins, peering into this box here and that bag there, losing myself on memory’s road and occasionally unearthing unexpected treasures.

So it was earlier this year when I discovered a box containing all of the maps, mementoes, and notes from my very first journey with GeoEx: a trip to Hunza, in northern Pakistan, undertaken in the spring of 1990, when I was the Travel Editor at the San Francisco Examiner-Chronicle, and GeoEx was known as InnerAsia Expeditions.

As 1990 dawned, I was feeling the need for some deeply personal, envelope-pushing adventure. The Bay Area was the center of the burgeoning adventure travel industry, and every week brought news of enticing new trips these companies were crafting. For years I had been especially enticed by the annual catalog of San Francisco-based InnerAsia Expeditions, whose exotic offerings comprised a destination dreambook. I also had been hearing rumors of a fabled place in northern Pakistan called Hunza. When I discovered that InnerAsia was offering a three-week adventure that went to Hunza and beyond, high into the Himalaya along the equally fabled Karakoram Highway, I immediately wanted to learn more. I contacted the company, and the more I heard, the more it sounded like exactly the adventure I was looking for. Before long, I had excitedly signed up.

This morning I retrieved that box and brought it into my study. I opened my tattered, coffee-stained journal and found the first entry from that long-ago journey. There, in scribbled, smudged blue ink, I read these words:

March 30, 1990; aboard Pan Am #66, en route from SFO to JFK:

I have been on this plane for four hours, during which time I have drunk coffee, coke, ginger ale, and lemonade, eaten a chicken-and-rice lunch, and read 104 pages of John Keay’s The Gilgit Game, and now I am feeling almost numb. I guess this is the blankness between leaving the familiar and arriving at the unfamiliar.

Four hours west of here are Kuniko and Jenny and our beloved pink home, my neighborhood, friends, and colleagues, my office—all the known world. And somewhere ahead of me—about 23 hours ahead, if all goes according to plan—is the great unknown: Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Peshawar, indescribable mountains and valleys and ancient, long-isolated cultures, rough, rough roads, new foods and smells and adventures unimaginable—Pakistan. The great unknown!

“The great unknown!” Three decades later, in 2020, at the end of nine long months of staying close to home, these words cast an enchantment. While I have been content to restrict my exploring to the wonders of the Bay Area this year, a part of me yearns to wander the far-flung corners of the globe again, to venture once more into that great unknown.

I emptied the box and before long had surrounded myself with Pakistan: I had the Nelles Verlag map of Pakistan on my right, the Road Map of Pakistan from Mr. Books Super Market Islamabad on my left, and arrayed all around me, Lonely Planet’s Hindi/Urdu phrasebook, postcards, brochures, my musty journal pages, shards of still-glistening stone in a crumpled brown envelope, and hundreds of photographs, plus the InnerAsia trip itinerary, equipment list, and notes for travelers.

Immersed in these runes, I was transported to 1990, and the mysteries and marvels of that life-changing adventure unfolded once again.

April 2, Pearl Continental Hotel, Rawalpindi:

I arrived in Islamabad this morning at 2:56 a.m. I left San Francisco at 11 a.m. on March 30 and flew a total of twenty-seven hours—via New York, Paris, and Frankfurt. Now, at last, I’m in Pakistan: At the airport, hot white letters spelling “Islamabad International” blazed in the darkness, and all around them the same words danced in neon blue Arabic script.

Five of the nine members of my tour, plus trip leader Tom Cole, were on the same flight from New York, and we introduced ourselves, stretched sore muscles, and rubbed bleary eyes while waiting for our bags to appear. Soon they did, as did our smiling local guide, Asad Esker, and driver, Ali Muhammad, who whisked us through the dazed and humid night to our luxurious recovery rooms at the Pearl Continental Hotel in nearby Rawalpindi.

I slept fitfully for a few hours, then was awakened at 4:30 by the distant wail of a muezzin calling the Muslim faithful—who comprise 99 percent of the population of Pakistan—to prayer. Now raucous crows’ caws fill the air, and the rising-falling song of another muezzin braids with the first. Suddenly sirens blare.

What’s going on, I wonder. A fire somewhere? Or maybe just the impending sunrise—for we have arrived during the holy month of Ramadan, when Muslims are not supposed to eat or drink between sunrise and sunset.

The dull cacophony continues, muezzins and sirens and crows wailing and blaring and cawing until it seems as if the whole country is speaking with one voice, and the just-waking day soars and swells and echoes with the sound of it.

Then a solitary soul, much closer, begins his plaintive call. The voice rises, holds, and falls. The words are clear and strong and imbue the air with a strange and powerful fervency and mystery. I think it’s a song of supplication and hope—but who am I to say?

I know nothing, understand nothing; everything is unfamiliar. I am a blank map, onto which Pakistan has just begun its artful scrawl.

* * *

Now it is the end of my first full day in Pakistan, and already I am bursting with images of this new world.

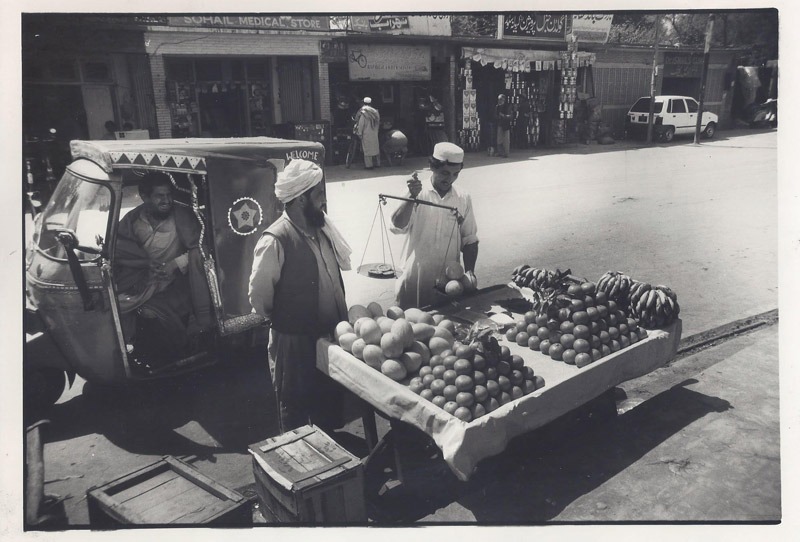

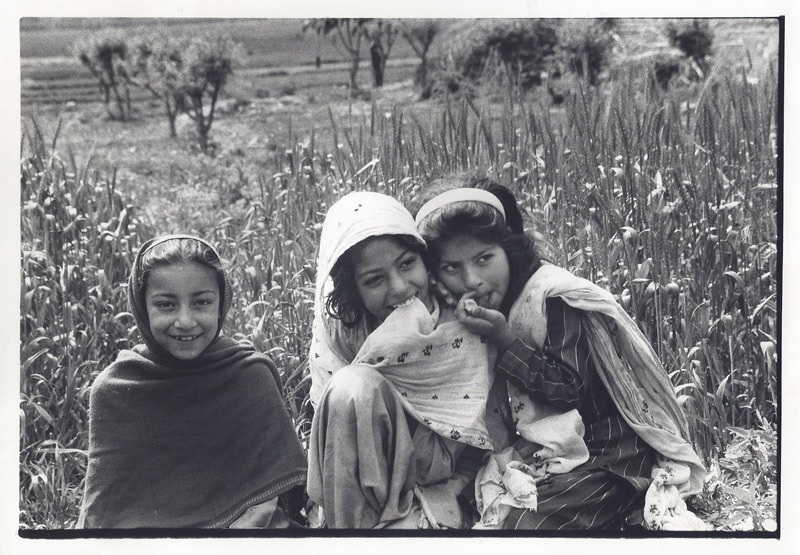

This morning, after an orientation session in the hotel lobby, our group set out to visit downtown Rawalpindi. My first impressions were of dusty streets loud with horns and crammed with buses, cars, carts, and bicycles. And people! Bearded, fierce-eyed men in turbans and shalwar kameez (the light and loose Pakistani suit that combines a knee-length shirt with drawstring pants); little children in dusty clothes, all big eyes and quick smiles; women wrapped in gorgeous veils and scarves and shalwar kameez, some covered completely from head to toe, others with only their faces exposed.

Children stood behind carts piled with pyramids of figs, oranges, or grapefruit; men sat in storefront shops selling electric fans, shoes, underwear, sewing machines. Alleyways twisted past stalls displaying jewelry, bright bolts of cloth, fantastic colored mounds of spices.

As we wandered, I quickly realized that my fundamental preconception of Pakistan was wrong: I had expected a miniature version of India, but unlike the Indian cities I had visited, here there were no beggars, and none of the vaguely menacing atmosphere of poverty, decay, and hopelessness I remembered from Calcutta and New Delhi. Wherever we went, we were either ignored or greeted with hearty smiles and hellos. And even in that chaos and cacophony, there was a sense of order and purposefulness; the shops seemed well maintained, and the adults seemed markedly attentive to the cleanliness of their clothes and the neatness of their appearance.

Already the map is being filled in.

April 3, Pearl Continental Hotel, Peshawar:

We flew this morning to Peshawar, the capital of Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province. Peshawar has been in the international spotlight because it is the headquarters-in-exile for the Afghanistan guerrillas who have been fighting the Soviets and the Soviet-instituted government in Kabul. Unlike Rawalpindi, Westerners are in evidence throughout the city—most, Asad said, either journalists or workers with one or another international aid organization.

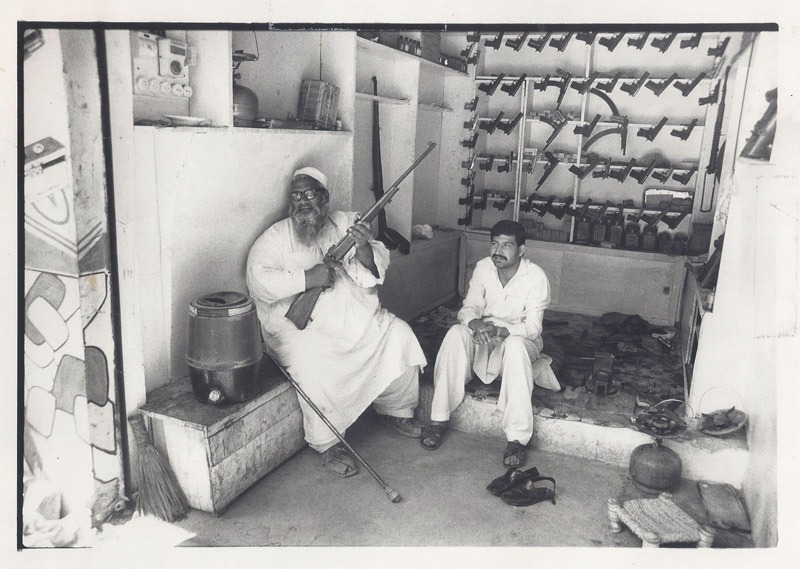

We began our tour with a quick exploration of the Peshawar bazaar. This manifested the same wonderland of colors, smells, and sounds as Rawalpindi’s, but made even more complex with the addition of the people and products of Afghanistan. Then we set out for Darra Adam Khel, which Asad described as the headquarters of Pakistan’s burgeoning gun-making and gun-smuggling industry. On a trip that promises a wealth of eye-opening revelations, this one was acutely memorable, and jarring.

On the dusty road to Darra, we passed scenes that already seem iconic snapshots: rough, mud-walled settlements that Asad said were Afghan refugee camps; women in flowing red and white robes balancing bright green packages on their heads; donkey carts bearing bricks; barefoot children in ragged clothes skittering through the dirt or hoisting slingshots, stopping to cry out and wave when they saw our foreign faces; eye-relieving splashes of green fields—wheat, sugar cane, and sugar beets—and stands of trees; scraggly cows and burros and sheep by the side of the road.

At one point, Asad explained that we were now passing into tribal territory, where Pakistani law stops and local law takes over. The tribes elect their own councils and representatives, he said, and essentially police themselves. An invisible corridor that extends forty feet on either side of the road is considered Pakistani territory; venture beyond that, and your fate is in the hands of the local tribes. “The gun is the law of this area,” he said.

And then we reached Darra Adam Khel.

At first Darra looked like any other dusty town, one main street and a few side streets lined with small shops. But something heavy hung like a shroud in the air. As we walked through town, we saw storefront after storefront, each one glistening with pistols, rifles, bullets, and knives—every variety of weapon one could imagine, all on neat display.

Later, I ambled alone along the dusty back alleys, watching old men and young boys patiently tapping and tinkering and polishing their creations like kindly Swiss toymakers. Suddenly the unreality of it all overwhelmed me, and I stopped and spoke into my tape recorder: “They don’t look like monsters; they’re just brothers, husbands, and fathers making money to buy flour and fruit and shoes. And yet I feel that I’ve touched the heart of some immense evil, the vital nerve center of a sinuous and shadowy network of smuggling/oppression/conflict that operates all around the world and is vastly more powerful and pervasive—and perverse—than I had ever imagined.”

This unfurling map is a complicated one.

April 4, Pearl Continental Hotel, Peshawar:

This morning we learned that we would have to alter our itinerary: Asad said that we could not fly to Chitral, gateway to the pagan Kafir Kalash people of Kafiristan, because seasonal thermal updrafts were making it impossible to land there. This kind of uncertainty is part of the adventure travel package—obstacles that sometimes no amount of money or preparation can overcome.

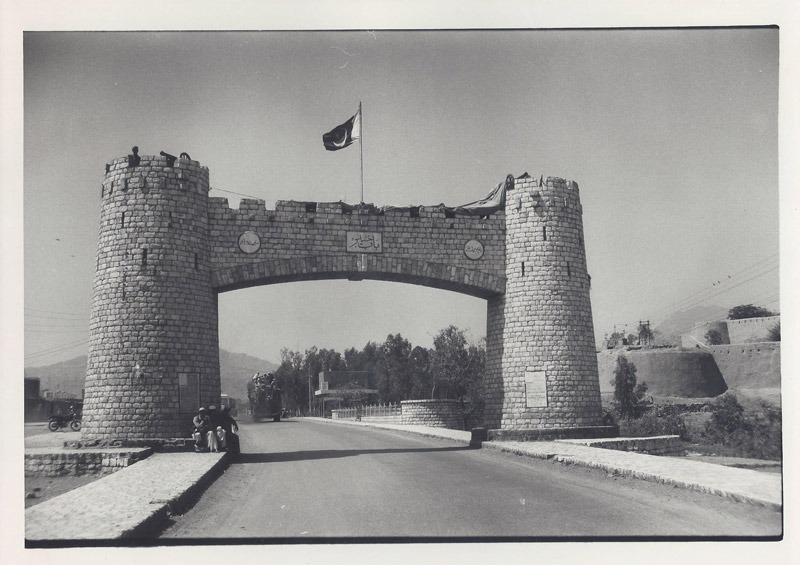

I was disappointed that we weren’t going to see the tribes of the Kalash, who reportedly have managed to maintain their own pagan beliefs and distinct dress, speech, and other cultural practices through two millennia of passive Buddhist belief and, later, aggressive Islamic rule all around them. But then Asad announced some good news: He had secured permission for us to visit the storied Khyber Pass, near the border with Afghanistan!

Martial music played and images from Gunga Din marched through my head as we wound due west toward the border. We passed two sprawling Afghan refugee settlements—temporary structures of mud, bamboo, and straw, stretching across the dusty flatlands—and Asad said that 35,000 people lived in one and 28,000 in another.

Until now, my sense of the Afghan war has been confined to television and newspaper reports viewed or read in the comfort of my living room. Now the picture has changed. Try to imagine all the inhabitants of Burlingame, say, or Los Gatos, living in these patched-together structures, laced by dirt lanes on a parched plain; then try to imagine providing for all their needs in a country that is already strapped meeting the needs of its own inhabitants, and then try to imagine the sufferings of the refugees themselves—from maimed limbs to splintered families to profound psychological displacement. Imagine all these, and you begin to get some sense of the scale and depth of the problems the Afghan war has created.

Along with the present, the region’s historic past came to vivid life as well. At one point we stopped and got out of our van, and Asad pointed to the ribboning road we had just traveled. “If you look closely out there, you can see three roads: On the top is the road the Mughals used in the early 16th century; below that—see the dirt trail—is the path the Greeks used under Alexander in the 3rd century BCE; and then there is the Grand Trunk Road the British made in the 19th century.”

Later we passed a honeycomb of small shops, and Asad said, “This is Ali Mastid bazaar—from the earliest days of the Silk Route, this is where the camel caravans would stop for the night. In fact, nomad caravans still do stop here.”

As we bumped along, I realized that I was being given a great gift: In the accumulation of images and encounters, as my feet scuffed that parched ground, as I nodded at Pakistani soldiers, shook Afghan hands in the bazaar, and waved to children in the settlements, the war was becoming personalized—it was no longer their war, but my war, too. And as the sun glowered down and the earth baked as it had when Alexander’s soldiers walked this way, I thought of how all wars are just people fighting people—and of how just as sun and wind inevitably shape landscape, so too do climate and countryside shape human character and culture.

April 6, Swat Serena Lodge, Saidu Sharif:

Yesterday dawned dark and drizzly, and we splashed through the muddy, puddling streets of Peshawar bound for the Swat Valley and the city of Saidu Sharif, ancient capital of the Kingdom of Swat. As we wound north, roadside images revealed the presence of the past in this slowly developing land: cultivated fields crisscrossed by rough-dug irrigation trenches, occasionally punctuated by walled compounds of mud and straw; children gathering branches and twigs in the rain; yoked oxen snorting through the mud; carcasses hanging in a market; men huddled around a makeshift fire in a shop.

The weather was not propitious for touring the Buddhist ruins and Alexander the Great-related sites of Swat yesterday, or again today, so instead we spent our time shopping. I am not a great shopper, and I dutifully but dispiritedly hefted melons, admired earrings and necklaces, and trailed fine rainbow-colored scarves through my hands—until this afternoon, when we stopped at the village of Khwazakhela.

There, in a dark, dingy closet of a shop, maybe eight feet deep by five feet wide, we discovered a wooden and leather arrow quiver, with the arrows still inside, that both the shop owner and Asad said was at least 100 years old. Then in a grimy corner, among lanterns and coins and cooking utensils, I found a 100-year-old drum and a 350-year-old leather shield.

I twirled an arrow and felt the prick of its cool metal tip. Then I turned the drum in my hands, studying how the leather had been stretched over the beautifully worked brass, running my fingers over the creases where the leather had been stretched, smelling the dust and sweat and age of it. I beat it—dust dancing into the air—and imagined tribal palms beating that same worn spot a century ago; the dull thonk, thonk and tum, tum echoed in my ears just as—I imagined—they had echoed in tribal ears through the years.

Then I took the rough shield and imagined a Pathan warrior 300 years ago gripping those same thongs, that musty, pocked, leathery disc—about as big as a woman’s floppy Sunday hat—the only thing between him and death.

The shop owner picked an old, rusted, curving sword off the wall and playfully swung it at me. I parried his thrust with my shield. His eyes were suddenly electric with mirth and interaction—understanding that spanned cultures, connections that spanned time.

April 7, Shangri-La Hotel, Chilas:

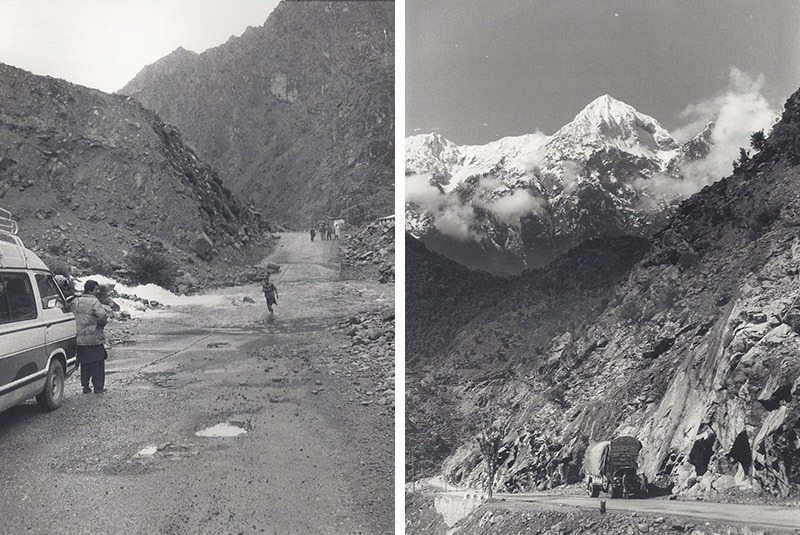

About two hours into our drive today, at a fraying, frontier-feeling truck stop called Besham, Tom Cole announced that we were at one of the most significant points of passage on our trip. From here on, we will be traveling along the legendary Karakoram Highway, or KKH, “one of man’s most magnificent and stupefying feats of engineering and endurance.” Undertaken jointly by Pakistan and China, the two-lane, 730-mile highway had taken twenty years to complete, with 15,000 Pakistanis and from 9,000 to 20,000 Chinese working on the project at any one time.

The KKH was dynamited and dug out of the mountains, Tom said, connecting Islamabad all the way to the Chinese border and beyond to Kashgar in the wastes of Chinese Turkestan. In some places the builders followed ancient trade routes that predated even the Silk Route; in other places, because of unresolvable property disputes, they simply blasted a way through virgin territory.

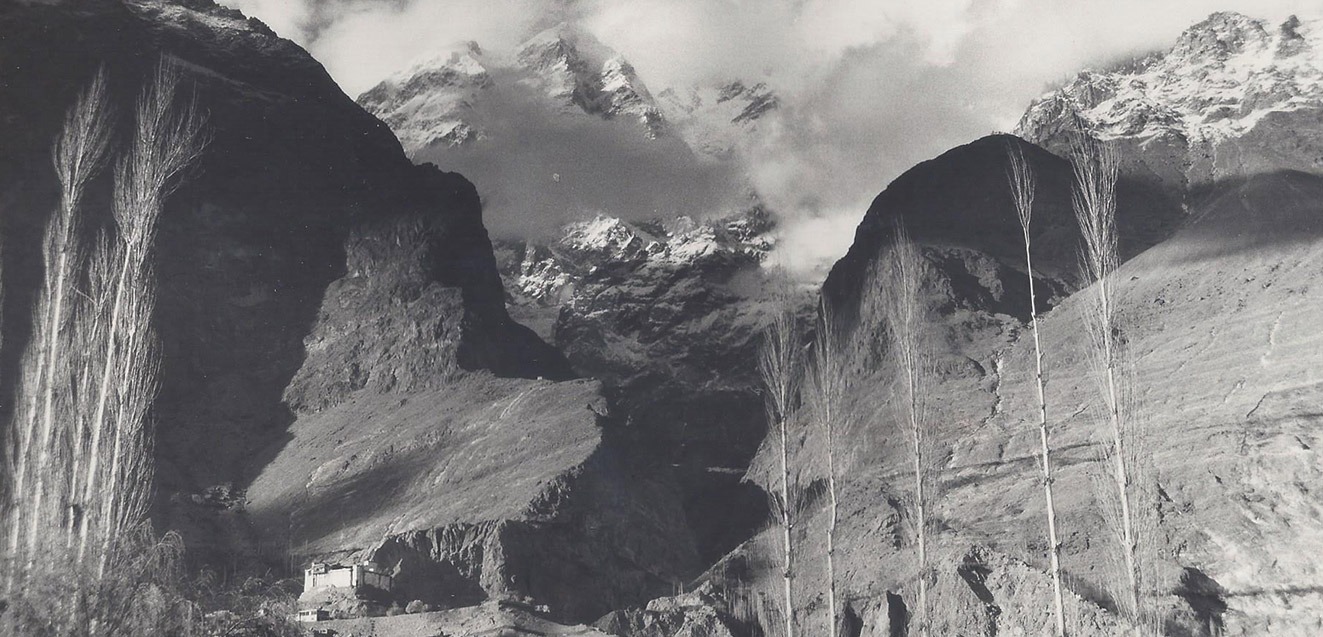

Soon after that stop, we wound into landscape as wild and uncompromising as any I have ever seen. The peaks rose steep and sheer—ragged in some places, sandpapered by colossal landslides in others—from the side of the road into the clouds. In all this immensity, the highway was a filament, a puny patch of pavement that nature could reclaim at any moment through any of the elements at its command: snow or mud, rock or flood.

When we saw nomads with sheep and cows walking by the side of the Indus River far below, they looked about as big as the period at the end of this sentence. I spoke into my tape recorder: “This is a landscape for gods, not men.”

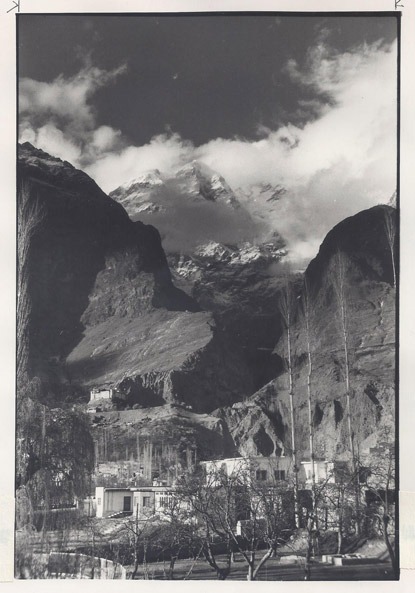

April 10, Mir’s Palace Bungalows, Hunza:

We are in Hunza! We reached Karimabad, the “capital” of the Hunza Valley, the day before yesterday, just before sunset. Of all the exotic stops on our itinerary, it is Hunza, famed for its apricot orchards, the longevity of its inhabitants, and its fairy tale setting of a verdant valley encircled by snowcapped peaks, that had most attracted me to this trip. In far-off California, I felt that something was waiting for me in Hunza, that something would be revealed to me here.

We started our tour yesterday with Baltit Fort. Built 550 years ago and inhabited by the rulers, or mirs, of Hunza until the present residence was built in the 1920s, this white, high-perched palace is a stirring sight, especially when viewed from a distance against a backdrop of cloud-piercing peaks.

Then we wandered around the valley, absorbing its sense of prosperity and serenity. Solid rock houses sit beside fertile green plots irrigated by an ingenious, extensive network of canals; and everywhere thin spring willows spire into the sky, and pear, apple, and apricot trees burst into brilliant pink and white bloom. Dusty, litter-free paths interlace the hamlets, and I noticed an aural interlacing as well: Because of the area’s acoustics, a child’s cry or the clanging of a cowbell at one end can be heard clearly at the other. It is as if everyone is everyone else’s neighbor.

Today dawned auspiciously clear. I woke with the sun, and at 5:30 a.m. Karimabad was surrounded by a spectacular panorama of peaks, each one glistening golden snow against the sky: Rakaposhi, Pari, The Throne, Ultar.

I decided to explore on my own today, and at 6:30 a.m. I walked alone down the main street, exulting at the invigorating air, the head-clearing silence, and the aloof but somehow encouraging solitude, serenity, and strength of the mountains. The entire valley seemed a soul-lightening composition of bold, basic colors: green fields, pink blossoms, white peaks, blue sky.

I spent the day in a kind of counterpoint of reflective solitude and entwining encounter. Wherever I wandered, I was met with smiles and waves, but I was also left free to simply roam and reflect.

At one point a man strode up to me and said, “How do you do? I am very happy to welcome you to Hunza. Would you like to see my house?” He gently took my arm and led me to a plot of land that had been leveled, where a cinderblock dwelling was sitting in stately half-completion. “This,” he said proudly, “is my house.” He took me through it room by room, pointing out the electrical outlets, the living room’s airy view, and the kitchen with its fancy new fireplace.

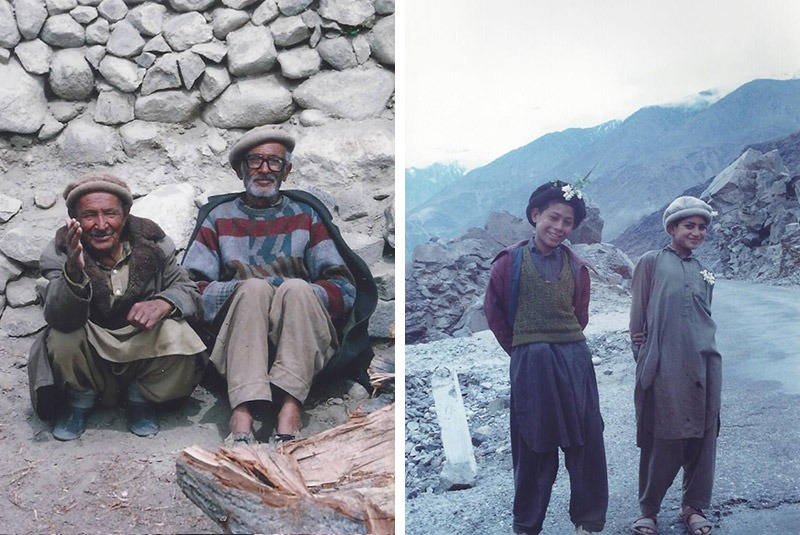

At another point I saw two old men sitting by the side of the road, in toothless tranquility. A young boy was standing near them, and I asked him how old they were. He asked them five times, raising his voice a little louder each time until finally he was yelling directly into one man’s ear. Then they nodded and responded with a stream of words. “They are not sure,” the boy translated. “Maybe eighty, maybe ninety.” The gentlemen looked at me and smiled great toothless grins.

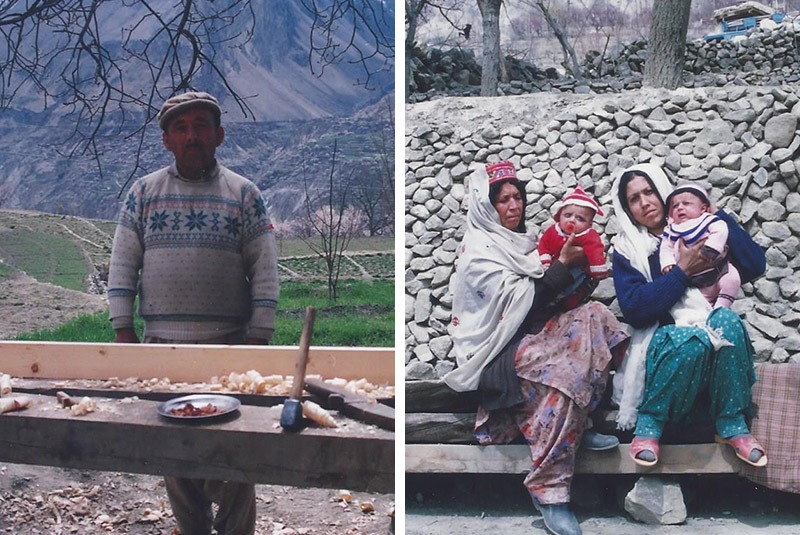

The encounter that moved me most of all occurred early in the afternoon. I was returning to the mir’s palace when I saw a man in his backyard crafting a beautiful wooden door. He was working slowly and carefully, and seemed so entirely absorbed that there was no separation between him and the wood he was shaping.

Suddenly he noticed me admiring his work and beckoned me to join him. I slid down a small hill to his home. He grinned. I grinned. I gestured that the door was very beautiful. He called out something, and presently a gorgeous young girl shyly walked up to me bearing a plate of apricots.

The apricots were sweet and delicious and I tried to say so. Then I pulled out some postcards of San Francisco and tried to communicate that it was where I came from. Finally I pulled out some pictures of my family and asked if I could take a picture of his family to bring home to show to my family.

His eyes lit up, and he called out something, and presently his family appeared—wife, teenage daughter, one baby, second baby, mother-in-law—peering out from inside the house. I asked if I could take their picture, and he enthusiastically motioned me into the house.

It was too dark and I didn’t have a flash, but I did have a chance to see the inside of a traditional Hunza house: We entered into the living room, which had a carpet and window at one end, a door leading into what I took to be a bedroom in another wall, a fireplace in the wall opposite the carpet and a hole in the ceiling above the fireplace, the perimeter of which had been blackened by smoke. Curtains of some rough cloth framed the window, but otherwise there was almost no ornamentation, nothing on the walls and no furniture save for one low chair.

After I had taken a photo inside, I asked if I might take their picture outside as well. They posed patiently and sweetly—the babies taking turns crying, drooling, and cooing—and when we had finished, the carpenter said something, and after a few minutes his elder daughter brought a plastic bag bulging with dried apricots and kernels.

These are for your family, he said, pointing to my pictures. I thanked him as profusely as I could, and handed him two of the San Francisco postcards I had brought. Please hang these on your wall, I said. He said thank you, then asked to have one of the pictures of my family as well. I hesitated—I didn’t know what situation might arise where I would need those precious pictures—but he was so kind and friendly and I was so moved, I relented and gave him his choice.

He chose a Christmas picture of us standing in front of a brightly decorated tree and told me that he would hang it proudly on his wall between the two postcards of San Francisco. He then clasped my hand warmly and said two words that I later found out meant “family” and “brothers.”

Now, at the end of this woven day, I think about this singular encounter. I wonder if someday my daughter will come to Hunza and find that same carpenter’s house, and our photograph still on that rough wall. And I think that time flows backward and forward, and that once in a rare while—if you are lucky and the universe conspires to help you see beyond your preconceptions—you stumble onto a connection that transcends it all.

April 11, Silk Route Lodge, Gulmit:

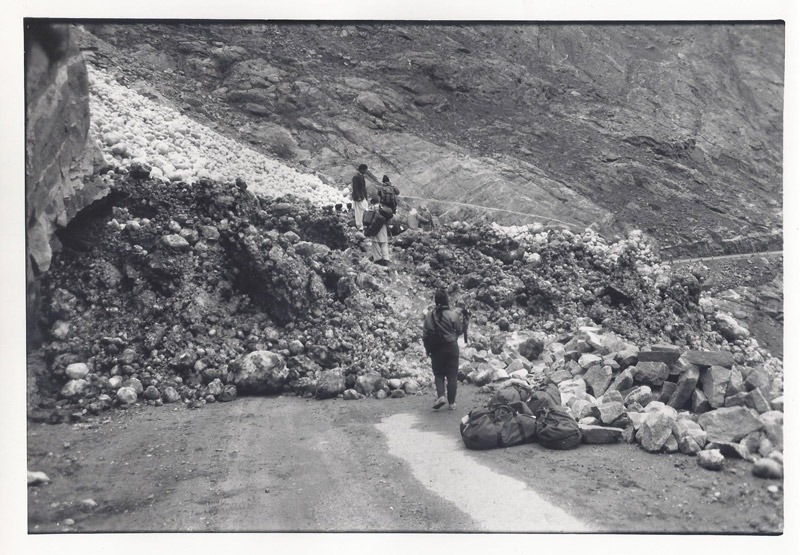

The adventures intensified today as we headed for Gulmit and the hot showers and hearty food other travelers said we would find at the Silk Route Lodge. The journey north was uneventful—waterfalls dousing the highway, rivers flooding the road, skitterish rocks, and precipitous drops have all become expected by now—until we reached an avalanche about 10 minutes from Gulmit.

The avalanche had buried the road long enough ago that a plow had already cut a corridor through its twenty-foot-deep drifts, but our steel-nerved driver, Ali Muhammad, feared the van would lose traction on the icy path and sit there, sandwiched in the snow, a fat target for a second avalanche.

So Asad set out on foot for Gulmit to get a tractor that could pull the van through, or some transport that could take us from the other side of the avalanche to the lodge, and Ali backed the van up to a point on the road that looked reasonably secure. And we sat and waited.

Waiting for an avalanche or rockslide to sweep us into oblivion quickly lost its appeal, so after a while, I decided to set out on foot for Gulmit, too. There wasn’t much chance of making a wrong turn—the nearest intersection was about four hours away.

Scrunch, scrunch, scrunch went my feet, quickly along the snow-plowed path, then slowly when I reached the other side. There, beyond sight of the van, the notion of solitude took on a whole new, almost otherworldly dimension. It was just me and the mountains, and I tried to imagine what the traders and missionaries and adventurers who had wandered this way before me had felt.

Scrunch, scrunch, scrunch.

If I walk long enough, I thought, I’ll reach the Chinese border. And if I keep walking after that, eventually this same road will take me to Kashgar, where right now wild-eyed mountain men are sizing up camels and crockery, bartering for boots and broadcloth.

Scrunch, scrunch, scrunch.

This is one of the most remote and desolate places I’ve ever been, I thought. If I were traveling alone, I would probably think I had come to the end of the Earth.

Then I took out my tape recorder and said: “It’s not just that it’s an inhospitable environment—which it certainly is—but also that you sense the forces of nature and time grinding on all around you, and you feel like a grain of sand on the slopes of one of the mountains.”

My voice seemed like an intruder, and I stopped—and listened. The silence was so overpowering, so absolute, that it was almost like a vacuum of sound. Instead of sound, enormous waves of energy emanated from the mountains all around, so strong that I had to sit down.

Perhaps Marco Polo felt these same waves, I thought. Perhaps he called his fellow adventurers to a halt in this very spot, and sat on this very rock, and pondered—just like me—what an insignificant piece he was in the world’s vast puzzle, how easily he could be bent, or lost, or simply worn away.

April 12, Serena Lodge, Gilgit:

After a revitalizing night at the Silk Route Lodge—where the meals were indeed excellent, although the hot water ran out before I could run into the shower—we returned by jeep to the avalanche and walked through it to our van. Then we rode south for about an hour—until we were stopped by another avalanche. This one had smothered the road like an overturned sack of sugar—a sack of sugar in which each granule was the size of a bowling ball.

This avalanche was so recent that it had not yet been plowed, but somehow the wizardly Asad had heard about it before we left the Silk Route Lodge, and had called his office in Gilgit to request that vans be sent to meet us on the other side of the snow.

We disembarked and hiked up, up, and over the avalanche—and lo and behold, two vans white as angels awaited us. Cries erupted from them at the sight of our group, and porters scurried forward to transport our bags over the avalanche’s hump. We chucked snowballs at each other in celebration.

On the rest of the long and winding road to Gilgit, we passed palaces, poplars, and petroglyphs, waterfalls and meeting halls, stupas and sheep, but for many the most exciting discovery was packets of British biscuits and chocolate cookies at a roadside stall.

April 16, Shangri-La Resort, Skardu:

After a heartening night at the Serena Lodge in Gilgit—heated rooms, delicious fried chicken, and custard desserts!—we journeyed on to Skardu. As it turned out, the weather began to clear during this all-day drive, and we were treated to spectacular vistas of brilliant snowcapped peaks and deep blue skies, puffy clouds and lush green terraced fields—the Pakistan of the guidebook pictures and tour brochure prose—before the end of the day.

This ride and subsequent day-trips to nearby villages and lakes have afforded me ample opportunity to reflect on this trip, and on some of the complexities of adventure travel in general.

One fact that has become apparent is that on a trip like this, adventure travel is exactly that: adventure. No matter how much money you have paid, rough conditions and travel unpredictabilities come with the territory, and so flexibility, tolerance, and good humor are absolutely essential.

Money does not buy certainty or guarantee comfort here. What it does buy is access, and that’s why people are willing to spend a hefty amount to go places they would have great difficulty going on their own.

A related issue is risk: I risk death every time I cross a San Francisco street or drive on a California freeway, I know, but the possibility of death by accident on Interstate 80, say, is familiar and so easier to ignore than the possibility of death by avalanche on the KKH.

Rugged, remote trips such as this one put the gift of life in a new perspective. I think what it all comes down to is this: Every day in our lives presents dangers of one kind or another; some we challenge because they are expedient, others because we judge that the rewards merit the risks.

April 18, Shangri-La Hotel, Chilas:

That last note has taken on new meaning now, two days later. We are sitting around a table at the Shangri-La Hotel in Chilas, debating what to do.

We drove here yesterday from Skardu, after learning that the Skardu-to-Islamabad flight would not operate that morning.

Heavy rains have been falling for at least 48 hours, loosening the rocks above the KKH and increasing the possibilities of avalanche or flood.

We have two options: If we leave now, risking the highway, we can reach Islamabad by midnight; this will give us a full day to recuperate before the 32-hour journey back to the United States. If we wait in Chilas, the rain may let up, which will allow us to drive more safely straight to the airport tomorrow.

Tom Cole says he thinks we should stay in Chilas. Asad says he thinks it will be all right to go.

Rain patters on the roof, and the grimy light of a cloud-covered dawn smudges the windows. If we don’t risk the road today and the rains continue, we face the distinct possibility of missing our plane in Islamabad and being stuck there for three days until the next scheduled flight—if we can get seats on that flight.

Now we sit around the table, thinking of appointments and commitments, dangers and delusions, imponderables and percentages—and, most of all, loved ones anxiously awaiting our return.

We look at each other long moments and then, as if with one voice, say, “Let’s go.”

April 18, on the KKH:

I have felt fear at various times in my life, but never as palpably and deeply as I do now. It sits round and heavy, a lead ball, in my stomach.

The van is silent as we drive slowly down the rain-slicked road out of Chilas. A coppery dryness parches my mouth, and I am gripping the van seat to keep my hands from trembling. . . .

It is 6:00 a.m. now and we have been bumping along through the morning mists for about a half-hour. We have not seen one other car or truck, and that is spooky. The reality of the KKH hits home—it is not something to be trifled with. . . .

It is 8:00 a.m. and we have proceeded this far without avalanche, rockslide, mudslide, or flood. Now the mists have begun to lift, and our spirits have begun to lift with them. A kind of exhilaration is beginning to take hold, a feeling of exploring a world no one has seen before us. We are trailblazing, opening up the KKH. Adventuring!

Once again we begin to exclaim at the vistas and peaks, at the trim stone houses and rock-bordered emerald terraces. . . .

Now it is 8:07 a.m. and a red bus with “Rawalpindi” written on the front has just passed us going in the opposite direction. The whole van is cheering—the road is open!

April 19, Pearl Continental Hotel, Islamabad:

From that point on, our journey was all downhill, so to speak. The sun shone, the peaks glistened, the clouds puffed, the road dried—occasionally waterfalls coursed across the pavement or we bumped over great gaping stretches where the road had been washed away, but these were trifles, good photo opportunities, footnotes to the epic of the KKH.

Now that we are safely settled in Islamabad and the end of the adventure approaches, I feel a mixture of exhaustion and exhilaration, and an almost unbearable nostalgia for the trip that I am still on. I think back to my bleary arrival on April 2, when I wrote, “I am a blank map, onto which Pakistan has just begun its artful scrawl.” That moment feels so long ago; that moment feels like yesterday. . . .

Three weeks ago, Pakistan was the great unknown; it meant nothing to me. Now it is all around me. Pakistan is burros burdened with fodder and wood; it is lush green fields dotted with big blossoms of color that, as I get closer, turn out to be women in red, green, purple, or blue robes. It is children with dark hair and big shining eyes who smile and wave and cry out, “Bye-bye, bye-bye,” and weathered men in white caps and dun-colored blankets, their stares like skewers until I smile and wave—and their wrinkles crease into smiles and they raise their hands in stately salute.

Pakistan is a string of camels plodding down the highway; young men in spattered shalwar kameez playing cricket in the rain. It is women washing their clothes in a river, and naked children playing jacks in the mud nearby. It is tiny, musty shops crammed with old artifacts and new handicrafts; open-air stalls selling oranges and dates, carpets and cloth, jewelry, spices, guns. It is painted trucks, horse-drawn carriages, battered bicycles, mountain palaces, and muddy refugee camps. It is white clouds and gray clouds; green fields and snowy meadows; dusty plains and snowcapped peaks; pearly mist and blue sky. It is all Pakistan. Pakistan!

Little did I know, three weeks ago, that I was beginning a journey that would have no end. . . .

December 6, 2020; Piedmont, California:

I sit in my study, immersed once again in this life-quickening adventure that taught me so much, stretched me so far, and challenged me in so many ways that I had never faced before. Simultaneously here and there, I feel inexpressibly grateful for this unexpected gift, that helped me define my path, and gave my days richness and meaning I had never imagined.

It was truly the adventure of a lifetime. And though I didn’t know it then, it was also the beginning of a lasting relationship with GeoEx, another adventure of a lifetime.

Now I stretch my arms to embrace all these runes around me, and think: We are all blank maps. Or rather, we make our own maps as we journey, in Pakistan and in life. We don’t know what the world will deliver us—cancelled flights, cloud-shrouded skies, avalanches on the KKH; ancient paths, snowcapped peaks, hand-clasping encounters with carpenters. All we can do is follow the compass of our heart, and open ourselves to the wonders of the open road. Then we may ride the high road to Hunza, and learn that wherever we are, we are already home.

Yours in abiding wanderlust,

Don George

* * * * *

Are there journeys that inspire you to wander down memory’s road? Or past travels that feel particularly life-defining? Please share your thoughts, memories, and photos in the comments section below! I love hearing from you! Thank you!

* * * * *

To find out more about our trips to Pakistan, call our travel experts at 888-570-7108 or inquire online.

Truly amazing and outstanding story we deeply appreciate your kind words for Hunza experience!

God blessed you!

F Karim

Such a interesting and sweet story about Karimabad Hunza. Thanks for sharing the story and hospitality of Hunza.

I am from Hunza but living in San Francisco from last couple of years.

Love both SF and Hunza 😊

Thanks again Mr George.

Waooo outstanding… enjoyed the vivid descriptions about different places… especially about Hunza Karimabad….. Thanks…

Do come to Karimabad someday and meet again the Carpenter’s family… I am sure they will love to welcome you again… Thanks.. God bless you..

Thank you so much for giving us such a moments of your journey 😊 The boys in arms of grandmother and mother are me and my twins brother whom house you visited in 1990 and the man uncle islam shah a carpenter who is working at my house at those times. A week back the carpenter islam shah left this world at age of 85 plus may his soul rest in eternal peace. And the lady on left also left this world on 2013 may her soul rest in eternal peace as well. Ameen If you ever visited again to… Read more »

Most deeply and warmly welcome to hunza and my home anytime 😊

Thankyou so much for your prayers and love.

I am grateful to meet you someday at my home! ❤️

Mail you send inbox was missed unfortunately. Kindly send back if possible i will reply as soon as possible Thank you 😊

Don- Your vivid descriptions of people, places and the expectation of “high adventure” reminds me of my trip to Pakistan in 1996 with Katherine Levenson (Top Guides, formerly with Inner Asia). We followed your intin. in reverse, beginning in Lahore with Humaira Kahn, the only woman guide (then) in Pakistan. She had guided treks and all-male motor cycle tours, yet her father wouldn’t allow her to travel alone on a plane. We were all women on that trip, except for Katherine’s 2 month old son, which granted us the opportunity to meet women of power and influence in Lahore and… Read more »

Your adventures stir my travel desires. I will read it again to try and absorb photos, the unknown world and your excellence with imagery of words. I cherish reading your adventure and have learned much. Congratulations!

Wonderful story – brought back memories of travels through this region. Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal – so many adventures including being caught in Tehran when the Shah fell (so many years ago now). We hitch-hiked from London to Istanbul – “Magic Bus” remember that – from Istanbul to Tehran where we ran out of options and into political curfews so got a ride up to the Caspian and wandered around there for a few weeks. Then got ride on an English double decker painted silver – owner was a completely mad Englishman but we had no choice – he… Read more »

WOW, your amazing journey brought back vivid memories of the (almost exact) itinerary I would follow 17 years later. This trip made such an impact that I thought about it daily for two years and even now, 13 years later, it has got to be one of my top adventures. Sadly, after 2007, the political situation destabilized and the the trip from Islamabad to Hunza on the KKH and on to Kashgar was no longer. I will have to take out my own trip notes now! Best regards.

Avalanches & uncertainty is true adventure….and looking back makes you appreciate it even more

Thank you for giving us this adventure virtually, Don! It also inspired me to remember walking the Camino in Spain. A way not as well known is the Camino Mozarabe which begins in Malaga. 2017 we walked Malaga to Cordoba, 2018 Cordoba to Salamanca, and 2019 Salamanca to Santiago de Compostela and then a bit beyond to Finisterre. It was life changing to walk an entire country from South to North. As we approached Santiago I felt what you expressed: “nostalgia for the trip I am still on”.

In 1987 we had quit out jobs and were backpacking around the world on those cheap round-the-world tickets you used to be able to get through “bucket” shops. We had on our bucket list to travel from Rawalpindi to Kashgar, China on what we had heard was a newly opened military road. But,it was really hard to find reliable information as to whether it was actually possible and if allow us to cross the Chinese border. It turned out it could be done and it’s still one of the highlights of all of the travels we’ve ever done. We slept… Read more »

Great story, interesting and enjoyable

Thank you, SO MUCH, for sharing the trip with us!! Hugs from this Grandma!! 😉

Don, thanks for sharing such a wonderful experience! Just waiting for the time we are all able to travel the world freely once again !

Hi Don,

I really enjoyed your blog on Pakistan and it brought back memories of the trip I took to that country in 1996. Thank you so much for your blog. I really enjoy your writing.